THE LOST EGYPTIAN

He was our trusted ally in the turbulent years before the Suez crisis. But when Mahmoud Sabri was abducted and faced the gallows, Britain failed to save him. Did an ugly secret lie behind his betrayal?

The night of November 30, 1952, a black Standard Vanguard left the safety of a British military complex at Ismailia in the Suez Canal Zone. The RAF staff car carried four men. One was English, one Palestinian, one Egyptian, and one of Scottish-Persian parentage. Under the light of a full moon they set out for the nearby Fayid airfield – and became the victims of a catastrophic ambush.

The road they travelled was plagued by merciless Egyptian nationalists, whose aim was to force the beleaguered British out of Egypt. Within hours the four were caught up in events that would involve the highest-ranking RAF officers, diplomats and government ministers. The incident contributed to Britain’s imminent military withdrawal from Egypt – which in turn led to the abortive Suez invasion, and drove a decisive nail into the British empire’s coffin. It also left a series of mysteries unsolved to this day.

The nationalists who targeted the four men were interested in only one, the Egyptian – Mahmoud Sabri, an inspector in the RAF auxiliary police. Sabri had links with Britain stretching back nearly 40 years, and it was his proud boast that he had fought alongside Lawrence of Arabia in the first world war. The inspector was to pay for his loyalty to Britain. He was spirited away by the ambush gang, and in the following months Britain shamefully turned its back on him. Eventually he was hanged, on the personal orders of Lt Col Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s future president. The kidnap also had far-reaching results for the other men in the car. Two fell under suspicion of selling Inspector Sabri to the nationalists for a cash reward. And one of them disappeared without trace.

At the wheel of the Standard that night was George McDouall, an acting corporal in RAF Security, a top-secret section with links to MI6. He liked to wear well-cut suits and was never seen in uniform or on parade. For missions into dangerous areas he often wore traditional Egyptian djellaba robes. He was in his late twenties and had been raised in Tehran by a Scottish father and Persian mother. His RAF colleagues knew him as “Persian George”. He was fluent in Arabic and many dialects – an invaluable skill in his shadowy world of spies and spooks. He could be reckless and was fearless. McDouall was dark-skinned, handsome and a notorious ladies’ man.

Alongside him sat a Corporal Spooner, a more matter-of-fact character with a distinct Birmingham accent. He and McDouall were a good team and often worked together on dangerous investigations. On that chill November night, both wore western-style plain clothes. Spooner probably cradled a Sten gun in his lap and carried a pistol in a holster. McDouall would have also been armed, probably with a Sten, and with his favourite pistol – a Colt 38 – carried in a shoulder holster or tucked into his trouser waistband. The four were driving through ‘bandit country’, where armed gangs often ambushed British servicemen. Guerrillas were known to stretch wire across roads to decapitate motorcyclists. Captured national servicemen had their hands and feet hacked off, and were thrown into waterways to drown.

One of the men in the rear of the Standard was Ali Moghrabi, a Palestinian who had been an RAF regular during the second world war but was now employed as an interpreter. Like McDouall, he favoured a well-cut suit, and he wore white spats over his brown shoes. The other back-seat passenger was Sabri, the only man in uniform. The inspector’s age was something of a mystery, but he had told the RAF his date of birth was August 6, 1897, making him 55 and by far the oldest man in the car.

Sabri’s history was fascinating. By his reckoning he would have been 17 at the start of the first world war and his military record reveals that he first served alongside British forces in France. He may even have visited Britain, prompting an interest in the country he was to serve for the rest of his life.

From France he was shipped out to take part in the failed Gallipoli campaign, and at the end of 1917 he was with General Sir Edmund Allenby’s expeditionary force in Palestine. By October of 1918 Allenby’s stunning series of victories had finished off the Ottoman empire. Allenby rewarded the young Egyptian for his efforts. In June 1918, Second Lieutenant Mahmoud Sabri, Infantryman 7112, was mentioned in dispatches for his “gallantry and devotion to duty”. His military record says he got two more “mentions”. Plainly Sabri was making his mark.

In the 1950’s, Sabri liked to tell his RAF colleagues how, during his service with the expeditionary force, he had come to the attention of Lawrence of Arabia. Egyptian forces were fighting for Lawrence as he helped to free the desert Arabs from Turkish rule. Sabri’s contacts with British forces gave him a useful command of English and he remained in touch with Lawrence during the colonel’s post-war diplomatic activities.

In the 1920’s, Sabri qualified as an engineer in Cairo, and from 1934 to 1938 he worked with Balfour Beatty on the construction of Iraq’s Kut barrage, which diverts irrigation water from the River Tigris. At the start of the second world war he was with the Royal Engineers in the Western desert and by 1944 he was a civilian engineer with the RAF in Egypt. In 1949, despite being in his fifties, he was held in such esteem that he was able to join the RAF auxiliary police with the rank of inspector. That role made him the sworn enemy of Egypt’s nationalists. From October 1951, guerrillas killed nearly 60 British servicemen and an unknown number of civilians in the canal zone. Egyptians working for the British were also targeted and were stopped from working on military camps. Officially, Sabri was a local labour trouble-shooter and the RAF auxiliaries in 1952, Ismailia where Sabri was nationalists knew him as “King Sabri”. They based until his kidnap that year believed he was a long-term spy for British intelligence and that in his role with the RAF police he arrested and tortured Egyptians. The latter was closer to the truth. Inspector Sabri had his own office at No. 3 Police Wing, which was part of the vast Moascar army base and the RAF police headquarters for the area between Cyprus and Aden. Sabri’s senior officers in the RAF made themselves scarce when their enforcer was questioning Egyptians suspected of theft or terrorist activity. He was a hard man who had his own ways of extracting confessions.

RAF auxiliaries in 1952, Ismailia where Sabri was based until his kidnap that year

Sabri was under strict instructions not to leave Moascar because the Egyptians had put a price on his head. On the night he went out with McDouall, Spooner and Moghrabi he was apparently ordered off base “to investigate a case of desertion”, with disastrous results.

RAF records say that on the return journey from Fayid, the Standard broke down and the four men switched to a taxi. Minutes later they were confronted with a sight dreaded by all servicemen travelling in Egypt. The headlights of the car showed a gang of armed men strung out across the road. If McDouall had been driving the Standard he might have risked accelerating through them. But it is believed the taxi driver obeyed their instructions to stop. One RAF report says the gang was “commanded by Egyptian army officers”, while another says the “armed party was headed by a notorious Egyptian agent named Serougi”. The Egyptians apparently knew exactly where the car would be on the road and who they would find in it.

Sabri and Moghrabi were hustled into the Egyptians’ vehicle which roared off. McDouall and Spooner were left to run for it, finding safety in the gate hut back at the Fayid camp.

A few surviving servicemen can still recall how Sabri’s kidnap caused consternation among his friends at No. 3 Police Wing. Yet the first reaction of the RAF – not knowing even whether Sabri was alive or dead – was to discharge him from the service and stop his pay. Only feeble attempts were made to protest at his kidnap. His destitute wife, Farida, was ‘advised’ to take her six children from the comparative safety of her home near the base to her mother’s house in Alexandria. Her hide-out was discovered by nationalists, who wrecked it and destroyed all her papers. She was forced to flee again.

There was no news of the Egyptian inspector for more than three months. Then a letter from Air Vice-Marshal John Gray at Ismailia to the Air Ministry in London said Sabri was known to be in Egyptian hands and “under confinement”. Gray – a Bomber Command veteran – said that an official protest about the kidnap was made to the Egyptian governor of the canal zone. He also made clear the RAF’s own impotence and his anger at the failure of British embassy staff to act on Sabri’s behalf. Gray said Sabri was “held in high regard by his superiors” and that “it is regrettable and not understood why the British embassy are unable to intervene”.

Gray revealed that the embassy had dismissively written off Sabri as “an

Egyptian national”. Even allowing for the attitudes of the 1950’s,

one can only

guess how that smug phrase must have shocked Sabri’s military colleagues.

What would Lawrence of Arabia have made of such a betrayal?

Gray's letter dated 11th March 1953

The air vice-marshal’s letter was also the start of what became a tortuous campaign to win financial help for Farida. Behind the scenes, the RAF apparently helped Farida visit Sabri in prison. RAF records say she found him depressed and unwell. Despite that, he managed to give her a note to pass on to the RAF asking if she could be given eight Egyptian pounds a month “to enable her to live and to support the children”. It was a modest request. Sabri had been earning £33 a month.

As Britain began to lose control of Egypt and prepared to withdraw, such little concern for Sabri’s plight as existed was overtaken by events. However, at the end of August 1953 another appeal was made on Sabri’s behalf to Egypt’s air-staff liaison officer. Could “consideration be given to Sabri’s release?”. The letter had no effect. On October 10, Sabri appeared before a revolutionary tribunal in Cairo, charged with treason, spying and torture. His trial rapidly descended into farce when it was announced that no prosecution or defence evidence would be heard. The tribunal judges retired to meet in secret and the sentence of death was given the following morning. On hearing the verdict, Sabri stood and shouted “We die, but Egypt lives!”

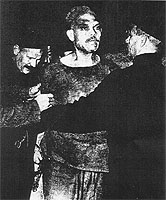

Sabri (in dark glasses) at the tribunal

Britain lodged one more protest but the effort was too late. “Concern” at the manner of the trial was expressed directly to Nasser through diplomatic channels but he ruled bluntly that the evidence was “conclusive and fatal”.

The next day at 8am, Sabri, wearing the customary red cap and gown of a man about to be hanged, was led from the condemned cell at Cairo’s Istinaf prison. His arms were shackled and he was barefoot. As two guards steered him towards a black-clad executioner, the RAF inspector loudly recited verses from the Koran. When the escort taking him to the gallows offered him a cigarette, he coolly refused, saying he had given up smoking. When offered water he replied “Thank you, thank you very much indeed”. The prison governor asked him if he had a last wish and Sabri replied that he wanted to say his prayers. Clutching a cleric’s hand, he repeated the verses “There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his prophet”. He did not flinch as he was taken into the execution chamber. Seconds later, the waiting witnesses heard the trap door crash open. But Sabri’s strong heart refused to give up easily. A doctor reported that it continued to beat for one minute and 55 seconds. Representatives of Nasser’s revolutionary government were at the prison that morning but they must have turned away with mixed feelings. They had defied Britain’s colonial authority and hanged a man they regarded as a traitor, yet Sabri did not allow them the satisfaction of seeing him break down. He had gone to the gallows with the name of Allah on his lips, and he died bravely – never recanting his devotion to Britain. It was a loyalty that Britain did not deserve. Nobody in authority ever paid tribute to Sabri’s work or to a loyalty to Britain that had lasted for almost 40 years.

Sabri seconds before his death

Back in Britain, the execution cause a brief stir. The public were more concerned with the Queen’s coronation, and Hillary and Tenzing’s conquest of Everest. Many gruesome episodes in the Suez campaign had already failed to make headlines, though Thomas Clayton of the Daily Express wrote a dispatch from Cairo criticising the British authorities for doing nothing to save Sabri. He prefaced his report with the words This is a story one Englishman is ashamed to write – and any Englishman should be ashamed to read”. The report did not make the front page.

During questions in the House of Lords, a telling point was made by Lord Killearn. He told the foreign minister, the Marquess of Reading, “that the execution of a man who has worked apparently for and with our armed forces, and who was apparently arrested in uniform, is hardly likely to encourage other Egyptians to collaborate with the British forces”. While not contradicting Killearn, the marquess hid behind the same weasel words as the British embassy in Egypt. He said “The noble lord must remember that this man was an Egyptian national and, as such, subject to Egyptian procedures”.

Farida had been too scared to take charge of her husband’s corpse and the remains of Mahmoud Sabri were interred in a charity cemetery. A month after his death, a letter from RAF HQ in Ismailia to the Air Ministry spelt out Farida’s predicament and said she was “destitute and very frightened”. It asked that any pension payment must be made in secret or Farida would be put in danger. Even then the penpushers at the ministry stuck to the rules and passed the problem to Treasury accountants – who quibbled over a payment of £8 a month.

Sabri and Farida had married in October 1949, when he was 51. She was a divorcee of 29 and already had four children. By the summer of 1952 they had added another son and daughter. Their youngest child was only three months old when Sabri was captured and the proud father must have died believing Britain had deserted him and his family.

Eventually the hard heart of British officialdom softened. A pension was paid to Farida, and monthly payments were made for the children while they remained at school. But it was not a large sum and doughty Farida battled for extra cash for her children. In 1961 she arranged for a letter to be written and secretly delivered by hand to the British diplomatic mission in Cairo. It is a heartbreaking message and tells of her repeated complaints on this meagre pension. She hopes for improved payments for the children and says “This will enable me to continue my educating and bringing them up in the proper manner that will ensure a good life. This for the sake of the 40 years of loyal and honest service which their father spent”. Farida made her mark on the letter with a thumbprint and the pension continued until her death at the age of 56, in 1976.

That might have been the end of the story. However, some of Sabri’s friends in the RAF still believe there was a darker, more sinister reason why some top brass and diplomats made such little protest on Sabri’s behalf. Senior RAF officers feared that whoever ordered the four men off base had an ulterior motive. They suspected that their inspector had been sold into the hands of the Egyptians. In view of that betrayal, was it too embarrassing to make a fuss on his behalf? Did the British fear the Egyptians might reveal that they had bought Sabri from a British traitor?

Sabri’s colleagues said the official explanation that the four went to RAF Fayid “to investigate a case of desertion” did not ring true. They said such cases were not security’s responsibility and the inspector would not had been risked in such circumstances. He did not deal with deserters, his responsibility was Egyptian troublemakers.

In a confidential letter to the Air Ministry the air attaché in Cairo tried to put the blame on Moghrabi – the man in spats. After the kidnap, Moghrabi had conveniently vanished and was never heard of again. Air Commodore Cyril Heard wrote: “Moghrabi……is believed to have been employed, or to have been coerced into assisting in the task of securing Mahmoud Sabri’s arrest”. But Sabri’s colleagues doubt that Moghrabi, a mere interpreter, could have persuaded Sabri to risk leaving the camp.

Other officers tried to put the finger on McDouall. Years later, back in Britain, an RAF police flight lieutenant who had been stationed at Ismailia met another Suez veteran by chance in a pub on the outskirts of London. Among the subjects for reminiscence was the strange case of Inspector Sabri. The flight lieutenant said McDouall had come under suspicion but no evidence against him had ever been found. The accusation surprised McDouall’s colleagues who remembered his bravery in exposing terrorists.

After Suez, the characters involved in Britain’s final flight from Egypt were quickly scattered far and wide. Many are now dead. Yet a few surviving veterans of the canal zone – some of them national servicemen bound to silence by the Official Secrets Act – feel guilt that a man who served our country for 40 years was abandoned in his hour of greatest need.

This Magazine Feature was written by Roger Wood

Sent in by Derek L Bradley

WHO WAS THE DRIVER?

George McDouall liked to tell his colleagues that his career in the RAF’s security section began in the urinals of a posh London club in the early 1950s. McDouall had been chasing girls in the bar when someone overheard him showing off his knowledge of the Middle East and its languages. When he went to the gents, a shadowy figure appeared at his side. The man said he needed workers who were fluent in Arabic. An appointment was made to meet the next day, and McDouall – who was a lorry driver at the time – was signed up. He soon found himself in Egypt, where nationalist guerrillas were regularly killing British servicemen who strayed from their bases. Virtually everyone was confined to camp. But not McDouall. His working life lay between the Special Investigations Branch of the RAF and the spooks of MI6. he acted with a freedom and authority beyond his rank of corporal. There is no official record of him being in the RAF at this time.

He was a flamboyant character. One day he returned to his base in Ismailia with a racehorse. After it had clattered round the parade ground, high ranking officers decided they had no use for a cavalry section, and McDouall was ordered to take it back. The same thing happened when he turned up with a large American Buick he had ‘liberated’. It was typical of McDouall, who seemed beyond the law. On one occasion he pushed his luck too far. With a handful of RAF pals he went to a small NAAFI canteen in the army section of the big Moascar base. McDouall had his eye on the attractive British girl running the bar and, as she bagged up her takings at the end of the evening, he persuaded her that the RAF contingent should “walk her home”. But a gang of army squaddies also had the girl in their sights. When they attacked the RAF men in a passageway between buildings, McDouall wasted no time. He yanked out the pistol he always carried and calmly shot the leading soldier through the groin.

George McDouall – the man at the wheel the night Sabri was kidnapped – with his racehorse

Even McDouall’s senior officers in the security section could not stop him being charged, and he was hauled before a court martial. But the officers were not beaten. They arranged for a top London barrister to fly out to Egypt. He arrived on the same plane as the judge and ran rings round the army’s prosecuting officer. McDouall – lounging confidently in court in a smart suit – was cleared on the grounds that he was protecting the NAAFI girl and her takings.

The NAAFI incident had its source in the frustrating shortage of women on the army and RAF bases. The few present were in huge demand for parties thrown by bored troops. Yet there was never a shortage of girls for McDouall. He always turned up with a lady on his arm, sometimes two. To the envy of colleagues, his partner at one birthday celebration was a glamorous Australian who was a passenger on a ship that paused in the Suez Canal. How he got aboard and then persuaded her to leave the safety of the vessel for a dangerous trip across Egyptian ‘bandit country’ in an RAF staff car was never discovered.

McDouall in classic pose at a party in Egypt.

It was no secret that the British spook loved the company of women.

McDouall became something of a legend. Yet at the end of the Suez crisis most of his colleagues lost touch with him. He told them he had plans to return to Persia. The names of McDouall and that of his sidekick, Corporal Spooner, never appear in the official RAF reports of the Sabri affair, and any written evidence they gave has long since disappeared.

CANAL ZONERS REMEMBER SABRI

Charles Agar- RAF Police Dog Handler

I was particularly interested in ’The Lost Egyptian’ article in

the latest magazine as I knew Sabri slightly. In 1948 he frequently was at RAF

Spinney Wood, Ismailia and was a good friend of the CO who was a Flight Lieutenant.

It was a Telecommunications Relay Station and I understand that he was a Big

Nebbie in the Civilian Labour network.

One evening in October six of us went to a cinema in Ismailia town and on the return journey on foot we encountered the usual harassment from a group of Egyptian youths. In the ensuing melee my watch was stolen but we got away more or less unscathed. Only the lads with me knew that my watch had been stolen but word had somehow got back to the CO as there were only around 50 men on the Station of all ranks and we were like a happy family. Next morning I was called into his office where he was with Sabri and I related the previous evening’s events and Sabri insisted on taking me to the Carricle (Police Station) on the Rue Negrelli to see if I could identify any of the youths concerned.

Sabri was certainly well received by the Police Chief. Of course, they never recovered my watch, unless some Egyptian policeman ended up with it but what I do recall quite vividly was the fact that Sabri always carried a small automatic pistol in his back pocket. A very wise and sociable man!

In 1952 the cinema newsreel in UK mentioned that Sabri had been executed by

the Egyptian hierarchy and I assumed that it was OUR Sabri

as I have never heard of that name either before or since.