POLITICAL CARTOONS

SUEZ: THE FORGOTTEN WAR AS SEEN BY BRITISH,

EGYTIAN AND ISRAELI CARTOONISTS

Elvis Presley had just recorded Hound Dog; in

May Manchester City beat Birmingham City in a legendary FA Cup Final that

left goalie Bert Trautmann with a broken neck; France recognised Tunisian

independence; later in June Polish workers were reeling after a failed uprising

in Pozman. Third class travel was abolished on British railways; £1

was worth $2.80.

On July 19 1956 news broke that heralded trouble;

Colonel Nasser of Egypt, meeting the Yugoslav leader Tito and Nehru of India,

was stunned to hear that the US – concerned about his pro-Communist

leanings – was suddenly withdrawing funding for the Aswan Dam, a giant

project to provide water for the Nile Valley and electricity for industry.

A world Bank contribution had been contingent on cash from Washington and

London, and therefore lapsed.

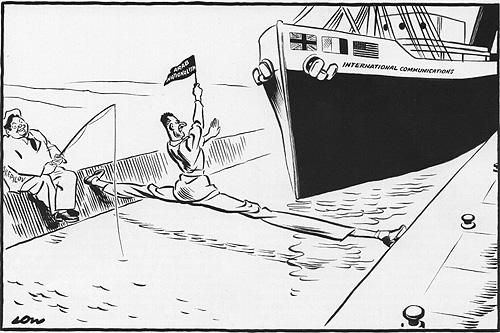

"- so nobody gives a dam", (Fig 1)

was the punning caption on a David Low cartoon published a few days later.

It was a subject the doyen of British cartoonists would return to all too

often as the Suez Crisis unfolded over the coming months – and marked

Britain and the world for ever.

People were used to Middle Eastern dramas, though

these were sideshows in the great Cold War confrontation. In recent years

there had been attacks on the thousand of British troops occupying the canal

zone. (Whitehall used the term "policing", though scores of Egyptians

had been killed in just one incident.) The last contingent was withdrawn that

June.

Fig 1: - so nobody gives a dam

David Low, July 25 1956, Manchester Guardian

American secretary of state John Foster Dulles withdrew

the offer to finance the construction of the Aswan Dam, partly in response

to Nasser’s purchase of arms from the communist bloc and his official

recognition of China. Nasser made political capital from the incident,

citing it as an example of the west’s lack of respect for his people

Nasser was already a familiar figure, preaching Arab unity and dignity under

his and Egypt’s leadership, denouncing the imperialists and the Zionists

who had conquered Palastine in 1948. handsome and eloquent, the young officer

who helped overthrow the corpulent King Farouk in 1952 had played a staring

role at Bandung, the conference of the Afro-Asian Solidarity Movement, and

went on to found the Non-Aligned Movement. His recognition of Communist China

- "Red China" as the Americans called it – was one reason

why the Aswan offer was withdrawn.

Egyptian tensions with Israel, then just a few years old, were familiar too:

in February 1955 the Jewish state retaliated for repeated cross-border guerrilla

raids, many by Palestinians, with a massive attack on the Gaze Strip. Egypt

counted 51 dead, the Israelis eight. That September Nasser announced a huge

deal securing tanks, guns and fighters from communist Czechoslovakia and mortgaged

Egypt’s entire cotton crop to pay for it. David Ben-Gurion, the Israeli

prime minister, began to prepare for war on his terms.

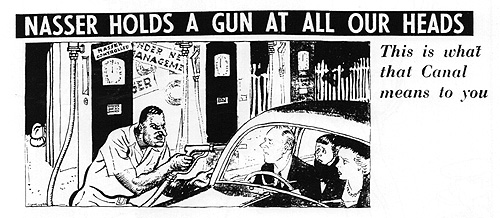

Nasser was a hero to millions of Arabs from Algiers to Aden,

but – like Muamar Gadafy and Saddam Hussein in later years – he

was widely portrayed as a bogeyman in the west, despite his flirtation with

the US until the Aswan rebuff, and even some exploratory secret contacts with

Israel.

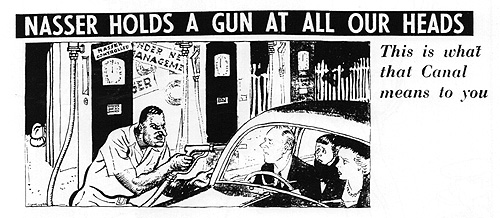

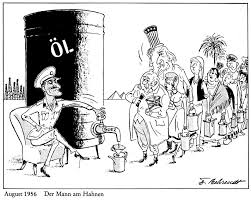

The Egyptian leader proved terrific copy for the cartoonists

of the day – posturing as he challenged the stocky figure of Ben-Gurion

with his wild hair and battledress, provoking the pin-striped, patrician-looking

British conservative prime minister, Anthony Eden. Egyptian motifs such as

camels, mummies, the Sphinx and the pyramids made for usefully humorous props.

The Humps of the Camel

George Butterworth, November 20 1951, Daily Dispatch

Despite Egyptian threats, the British Government insisted on retaining

control over the Canal much to the disappointment of King Farouk. During

the early 1950s, there had been repeated attacks on the British troops

occupying the canal zone.

Egyptian Tomb (King Thug AD 1952)

George Butterworth, January 23 1952, Daily Dispatch

Martial Law was introduced in response to widespread riots against

the British. Within 10 days, 6000 additional soldiers , 170 tons of

stores and 330 vehicles were air-dispatched to the region, the swiftest

ever mobilization of British forces in peacetime.

Many Brits, especially ex-servicemen, knew Egypt from the second

world war and long before – the “bints”, “shuftis”

and “khazis” of popular slang vivid reminders of a link that went

back 80 years. Ironically, Britain had at first opposed Ferdinand de Lesseps’

feat of engineering for fear it would only help the French. But in 1875 Disraeli

spent £4m to acquire a 44% stake in the Universal Company of the Suez

Maritime Canal – securing for the Empire a strategically vital 5,000

mile shortcut in the sea route to India and the Far East.

There had long been concern that Nasser might one day target

the canal. And Eden had developed an obsession with him. It got worse in March

1956, when Jordan’s young King Hussein, fearing nationalist unrest encouraged

by Egypt, suddenly sacked the veteran British General Sir John Glubb “Pasha”

– commander of the Arab Legion. Privately the prime minister told a

colleague he wanted Nasser “destroyed”. MI6 tried to oblige.

But the shock was real enough when on July 26 Nasser gave his answer to the

“betrayal” over Aswan: Egypt was nationalising the canal company

and freezing its assets. It would use its revenues to finance the dam. The

imperialists, he boasted in a speech to huge crowds in Alexandria, could “choke

in their rage”. Aneurin Bevan, the Labour politician, described later

how this looked at the time, even to those who ended up opposing war; “If

the sending of one’s police and soldiers into the darkness of the night

to seize somebody else’s property is nationalisation, Ali Baba used

the wrong terminology.”

Legally, however, Nasser was perfectly within his rights: the canal itself

had always been Egyptian territory. Nationalisation meant buying out the French

and British shareholders in the company, whose 99-year operating lease had

in any case been due to expire in 1968. He also guaranteed freedom of passage

– though not to Israeli ships, or to foreign ships bound for Israel.

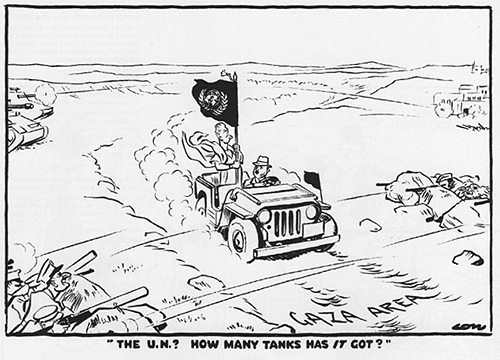

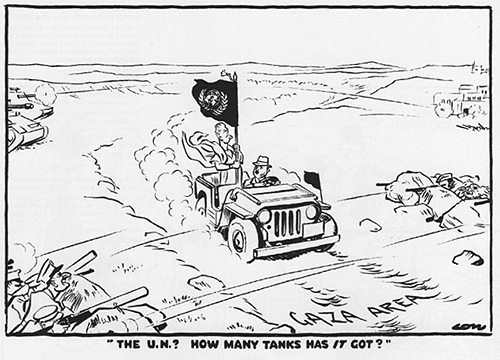

The UN? How many tanks has it got?

David Low, April 10 1956, Manchester Guardian

Egyptian tension with Israel – then just a few years

old – centred on the Gaza Strip. Egypt’s blockade of Israeli

shipping in the Suez Canal and Gulf of Aqaba intensified the hostilities.

According to David Low, “The United Nations worked hard but could

find no climate of peace in Israel. No one could decide what should be

done or how to determine the aggressor if real war came

That cut little ice with Eden. In London that evening the

prime minister was hosting a white-tie and tails dinner in Downing Street

for King Feisal of Iraq, keystone of the British-backed Baghdad Pact, and

a barrier to Soviet penetration of the Middle East. Iraq’s Prime Minister,

Nuri Said, the most pro-western of Arab leaders, had some blunt advice: “We

should hit Nasser hard and quickly,” he counselled. A dictator such

as Nasser could not be allowed to “have his thumb on our windpipe”,

Eden insisted.

Newspapers were soon screaming about parallels with Hitler

and Mussolini, the annexation of the Rhineland and the seizure of the canal

– echoing the disastrous policy of appeasement of the 1930s (opposed

by Eden) that ignored or downplayed Nazi and fascist intentions. Nasser’s

“Philosophy of the Revolution” had already been compared to Mein

Kampf. Low’s “The Colossus of Suez” (below) gave a cooler

interpretation of this mood, with a picture of a giant Nasser astride the

narrow canal.

The Collossus of Suez

David Low, July 31 1956, Manchester Guardian

Nasser retaliated against Britain and America’s refusal to fund the

Aswan Dam

project by nationalising the Suez Canal

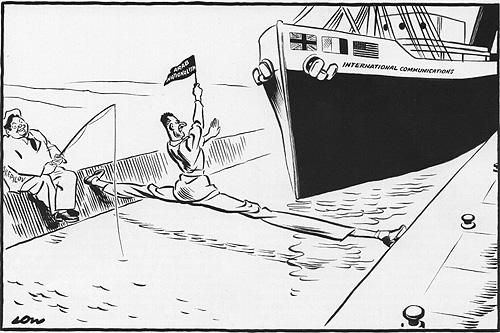

But from the start this was far more than an

obscure foreign policy issue; the cartoonist quickly addressed concerns that

the crisis could mean the return of conscription. And there were soon worries

about the prospect of petrol rationing; two-thirds of western Europe’s

oil came through the canal; to ship it round the Cape would cause a vast increase

in tanker costs.

Leslie Illingworth, July 30 1956, Daily Mail

Outrage in London and Paris triggered immediate

diplomatic and military moves. One July 30 the Admiralty and the War Office

announced what they coyly called ‘certain precautionary measures of

a military nature’ to strengthen Britain’s position in the eastern

Mediterranean.

France, seething at Nasser’s support for

the FLN rebels fighting for Algerian independence – and fed a stream

of tantalising intelligence by the Israelis – was far more gung-ho from

the start, and already supplying arms to Tel Aviv. But John Foster Dulles,

the US secretary of state, repeatedly counselled caution – setting the

tone for a hardening view from America as events unfolded. With an election

in November, President Eisenhower wanted no distractions abroad.

On the British domestic front, at that stage,

there was a measure of unity. Hugh Gaitskell, the Labour leader, told the

Commons in its first Suez debate on August 2 that he did not object to those

“precautionary measures”. But he did recall that Britain was a

signatory to the UN Charter and must avoid breaching international law. “We

must not, therefore, allow ourselves to get into a position where we might

be denounced as aggressors in the Security Council,” he urged. They

were prophetic words.

August, September and October were taken up by

much high-pressure but ultimately fruitless diplomacy. Britain, France and

the US convened a conference of concerned countries to draw up an international

administration for the canal. On August 16, when it began at Lancaster House

– with Egypt conspicuously absent – the cartoonist Osbert Lancaster

came up with a clever if obvious line about being up a creek – or canal

– without a paddle. He was right.

“Your poor uncle is dreadfully depressed

– he keeps referring to the Canal as some

creek or other and says we are right up it without a paddle!”

Osbert Lancaster, August 16 1956. Daily Express

A conference organised by the British Government about the Suez crisis

was held in London with US secretary of state, Dulles, as moderator.

It proposed letting Egypt own the canal company but submitted its operation

to international control. Eighteen countries – controlling 95%

of Suez shipping – supported this plan. Four opposed it –

India, Ceylon (later Sri Lanka), Indonesia and the Soviet Union. Eisenhower

declared that the US would only support a peaceful solution, thereby

undermining the proposal. Nasser, obviously, refused

Nasser rejected the conference proposal as presented by Sir

Robert Menzies, Australia’s prime minister, on September 3. “The

situation is very grave,” Menzies reported. The initiative had already

been undermined when Eisenhower declared that the US would support only a

peaceful solution, helping get Nasser off the hook, “tragedy no. 1”,

in the pained words of Selwyn Lloyd, the Tory foreign secretary.

With the political temperature at home rising steadily, the

government announced a new plan for a “Suez Canal Users Association”

that would require Egyptian cooperation. The arrangements did not look robust.

Dulles gave the plan his support, but added that if the Egyptians should resist,

no American ship would be allowed to ‘shoot its way through’.

That was “tragedy no. 2” for Lloyd. Still, just 10% of the revenues

were to go to Egypt – hardly a glittering incentive for Nasser.

Sssh! Not in election Year!

David Low, August 8 1956, Manchester Guardian

Campaigning for re-election under the slogan “prosperity and

peace”, President Eisenhower refused to support an Anglo-French

military intervention in Egypt. Secretary of State Dulles had commented

that “we do not intend to shoot our way through”

Labour was becoming increasingly alarmed by the obvious ambiguities

in Eden’s approach. It Egypt refused to go along with the plan, the

prime minister warned in the Commons on September 12, it would be in breach

of the 1888 Convention governing the use of the waterway. “In that event,”

he said, “the British government and others concerned will be free to

take such further steps as may be required, either through the United Nations

or by other means, for the assertion of their rights.” He would, he

pledged, go to the UN “except in an emergency”.

Nasser’s nationalisation, meanwhile, had been implemented,

but ships, including British ones, were still getting through the canal on

time, and without the help of the experienced foreign pilots employed by the

company – debunking the condescending suggestion that the Egyptians

could not manage it alone.

In early October diplomacy shifted to the UN. But with Russia

leading opposition in the Anglo-French proposals, London and Paris began to

hone their military plans – though (and this is crucial to the whole

story of Suez) an emerging French idea for a clandestine link with Israel

was not public knowledge. It took over 40 years for the whole story to emerge.

On October 16 Eden and Lloyd met Guy Mollett and Christian

Pineau, their French counterparts, in Paris. The same day the French navy

intercepted a yacht named the Athos, off the coast of Morocco. It was carrying

70 tons of weapons for the FLN and had sailed from Alexandria with the help

of Egyptian intelligence. It was the Israelis who tipped off the French –

hardening the anti-Nasser mood in Paris.

Unknown to the public in Britain and France – and even

to senior diplomats in both countries – it was now that the plot really

began to thicken. On October 24 representatives of France, Britain and Israel

met in great secrecy at Sevres outside Paris. Ben-Gurion, Pineau and Lloyd

were the most senior figures. After three days of talks the parties signed

a protocol: in it Israel undertook to attack Egypt, and Britain and France

to invade Egypt on the pretext of separating the combatants and protecting

the canal from them. That childishly transparent fiction was at the heart

of the famous “collusion” that will always be a byword for Suez.

The Israelis were to get naval and air support while their forces destroyed

Egyptian forces. Eden ordered all copies of the protocol destroyed. The one

copy that survived did not resurface unit 1996.

Nasser prepare

Abu, September 2 1956, The Observer

Initial events followed the plan: war began on

October 29 with Israeli paratroopers occupying the Mitla Pass in Sinai, 24

miles east of the canal, bypassing the Egyptian defences. An Anglo-French

ultimatum followed, threatening intervention if the belligerents did not withdraw

from the waterway. The Manchester Guardian called the ultimatum “an

act of folly, without any justification in any terms but brief expediency.

It pours petrol on a growing fire. There is no knowing what kind of explosion

will follow”. The ultimatum was rejected the next day, on cue, by a

defiant Nasser. The Israelis, following the Sevres script, complied.

Israeli forces had already occupied Gaza and

went on to take most of the peninsula, capturing thousands of prisoners and

large quantities of weapons. They called it the “Sinai Campaign”.

For Egypt and the Arabs it was, as remains, “the Tripartite Aggression”.

French pilots flying Mystere jets with their insignia painted over provided

cover for the Israelis. There were suspicions of this at the time but the

first confirmation came later from Manchester Guardian correspondent, James

Morris, reporting from Cyprus to avoid Israeli censorship

Suez war preparations

James Friell (Gabriel) September 4 1956, Daily Worker

On July 30, the Admiralty and War Office had announced what they coyly

called “certain precautionary measures of a military nature”

giving rise to immediate concerns over the return to conscription. However,

despite the talk of military action, there seemed little urgency about

recalling parliament

Unease in Britain exploded into open anger. Gaitskell denounced

the government for abandoning the principles of British foreign policy. Lloyd

was asked directly in parliament whether there had been “collusion”

between Britain, France and Israel. “There was no prior agreement between

us about it”, he lied.

Keep to the right – and straight

on –

David Low, September 12 1956, Manchester Guardian

The ominous and death-like figure of Destiny shows Eden the way

Rock ‘n’ roll

David Low, September 15 1956, Manchester Guardian

Nasser rocks the boat which carried him, Mollett and Eden

Overnight the RAF bombed Egyptian airfields.

“The rat that had begun to smell … was now stinking to high heaven”

wrote Anthony Nutting, who was about to resign in disgust as foreign office

junior minister. The UN passed a US-sponsored resolution called for an immediate

ceasefire and the withdrawal of all forces.

It was against this stormy background that the

main Anglo-French operation – Operation Musketeer- lumbered into action

on November 4. As the cabinet met to approve the final decision, a mass rally

was held in Trafalgar Square under the banner “Law not War”. Cries

of “Eden must go” could be heard in Downing Street as the crowd

marched down Whitehall. The following day, as British and French paratroopers

were being dropped and Port Said bombarded, the Manchester Guardian called

for the removal of the government. “Sir Anthony’s policy, however

sincerely intended, has been hideously miscalculated and utterly immoral,”

its editorial said.

Remember, remember

Abu, November 4, 1956, The Observer

Eden is portrayed as Guy Fawkes

Provocation

David Low, November 9 1956, Manchester Guardian

Eden warned that if Egypt did not support the “Suez Canal Users

Association”, it would be in breach of the 1888 Convention governing

the use of the waterway. “In that even”, he warned, “the

British government and others concerned will be free to take such further

steps as may be required, either through the UN or by other means for

the assertion of their rights.” Under pressure from the Americans

and the UN, the British declared a ceasefire on November 6 although

the entire Suez zone had not been captured. By mid-November, UN peacekeepers

were arriving in Egypt

A British radio propaganda station, broadcasting from Cyprus,

urged the Egyptians to surrender. Resistance was fierce but short-lived. Estimates

of Egyptian casualties ranged from 750 to 2,500. The British and French forces

suffered 22 and 10 dead respectively. It all provided a perfect distraction

for the Soviet Union, which had just invaded Hungary to crush the revolution.

Khrushchev threatened a nuclear attack unless London and Paris backed down.

The Egyptians sunk ships, bridges and floating cranes to block the canal and

Port Said harbour, making a mockery of the whole free navigation exercise.

Eisenhower was livid, protesting he had been “double-crossed”.

US officials were ordered to cut off all contact with their British counterparts

and raised the prospect of oil sanctions, Most damagingly, the US refused

to support a suddenly vulnerable pound. Bankruptcy threatened unless the US

Treasury or the IMF provided a short-term loan. Ike said no. Eden agreed to

a ceasefire on November 6.

Eden still insisted he had been right to act. "We did what the UN without

a police force could not do in time," he said. By mid-November UN peacekeepers

were arriving in Egypt. On November 21, suffering from exhaustion, the prime

minister flew to Jamaica to recuperate. In early December he agreed to withdraw

the troops. France and Israel followed suit. An IMF loan of $560m was approved.

On December 20 he followed Lloyd in lying directly and brazenly to the Commons:

"There was no foreknowledge that Israel would attack Egypt – there

was not." It was the last time he spoke in parliament.

The inevitable came on January 9 1957. Eden resigned. He was

replaced by Harold Macmillan. "Sunk off Suez" was the caption under

Low’s drawing of a capsized ship in the canal, it’s "go-it-alone"

flag just visible above the water, watched by a haggard-looking prime minister

Egypt, under a triumphant Nasser, reopened the canal the following April.

It was the end of what has been called "Britain’s moment in the

Middle East". It was also, as Nutting put it, borrowing from Kipling,

"no end of lesson". And it was one that a later generation was to

remember when another British prime minister, working with, not against, the

United States, became embroiled in another highly controversial war in the

Arab world.

Ian Black, the Guardian

July 2006

Tory party division. He wanted

to destroy Egypt – but ended up destroying his own party

Sarokham, November 13 1956, Al-Akhbar

Newspaper

Eden impales Churchill as he wields a pick

at Egypt

Eden standing in the midst of ruins - economic

crisis, Tory party division, relationship with US, Baghdad pact, British

reputation

Sarokhan, November 18 1956, Al Akhbar Newspaper

The Labour party had suggested offering compensation

to Egypt. In this cartoon, Eden asks Gaitskell, "what do you mean

by compensating Egypt, the ruins I have are the ones that need compensation"

Petrol Prospects

David Low, November 23 1956, Manchester Guardian

It has become increasingly difficult for the British government to deny

its collusion with Israel and France – Gaitskell accused it of abandoning

the principles of British foreign policy. The Tory foreign secretary,

Selwyn Lloyd, was asked directly in parliament whether there had been

‘collusion’: "There was no prior agreement between us

and about it.", he lied

Letter from home

David Low, December 7 1956, Manchester Guardian

On November 21, an exhausted Eden flew to Jamaica to recuperate leaving

the Leader of the Commons, RA Butler, in charge of the Cabinet. In early

December, he agreed to withdraw troops, and France and Israel soon followed

suit.

Eden is stained with failure:

"This stain is indelible. Only petrol can remove it, but there

is none."

Sarokhan, December 12 1956,

Al-Akhbar Newspaper

In early December, Eden withdrew his

troops from Egypt, and France and Israel followed suit. Shortly afterwards,

he lied to parliament about the covert operation. "There was no

foreknowledge that Israel would attack Egypt - there was not."

The "petrol" reference relates to Nassar's blocking of the

canal and the resultant oil shortage

Sunk off Suez

David Low, January 11 1957, Manchester Guardian

On January 9, Eden resigned as prime minister, allegedly due to ill

health. In the previous month, he had followed his foreign secretary

Lloyd in lying to parliament saying "there was no fre-knowledge

that Israel would attack Egypt – there was not". In his memoir,

Full Circle (1960), Eden continued to deny any collusion over Suez and

to justify his actions.

Suez Group

Abu, January 13 1957, The Observer

On January 9 1957 Anthony Eden resigned as prime minister on grounds

of ill health. His chancellor, Harold Macmillan, succeeded him ahead

of the favourite for the post, Rab Butler. The Observer’s political

correspondent reported that the influential rightwing Conservative backbench

Suez Group’s ‘hostility’ to Butler had played a role

in Macmillan’s appointment. Thus Abu sees Macmillan arriving at

his new home and immediately facing the consequences of the riotous

party that had helped him get there.

Were you sent….

Ian Scott, March 12 1957, Daily Sketch

In March, under the supervision of a United Nations police force,

the Suez Canal was cleared of wreckage and opened to shipping.

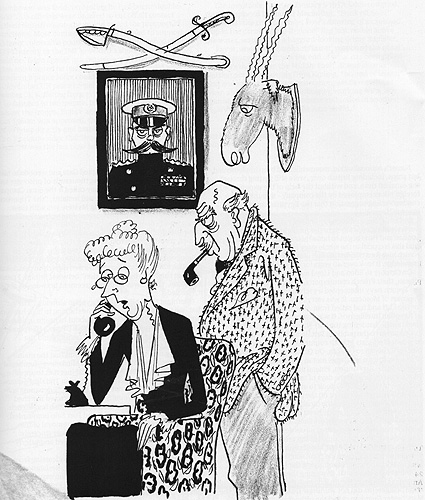

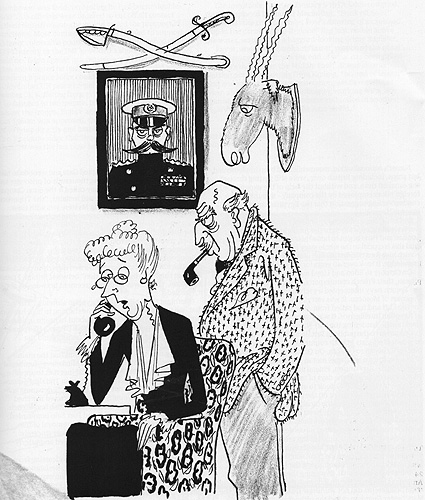

My kingdom for a horse

Abu, April 15 1956, The Observer

The Observer was constantly critical of the British government policy

on the developing Suez Crisis culminating in an editorial on November

4 spelling out its dissent; "We had not realised that our government

was capable of such folly and crookedness." In this cartoon Eden

is portrayed as Richard III fighting on with a broken sword and without

a horse with suspicious-looking US Secretary of State Dulles riding

past in the background. On April 15, The Observer’s Washington

correspondent, Richard Strout, reported the diverging strategies of

Britain and the US over Middle Eastern policy, with the US "pushing

the rather desperate hope of a United Nations solution … before

considering direct military action".