No. 10 MOTOR TRANSPORT REPAIR UNIT

El Firdan, Egypt January 1948

As Remembered By AC1 Don Studman 1946-48

(Continuing his journey after being stationed at RAF Shallufa - please see RAF Shallufa for the first part of the story)

On the morning of our departure from Shallufa I was issued with a temporary driving licence (no idea why!). I was already holding a permanent 1629 RAF driving licence issued by the transport sergeant at No. 5, the clerical chaps always seemed to get things wrong – I was often being listed as AC2 but on my pay book was AC1, thankfully I was listed correctly with pay accounts. On my papers it stated that I was to drive a Chevrolet 3 ton RAF No. 100351 from RAF station, Shallufa, to No. 10 MTRU RAF El-Firdan. We no longer had ‘old faithful’, the Leyland Coles Crane, it had never been seen since our arrival at Shallufa. (I presumed the W.O. emptied his boxes before it disappeared! If not someone would have had a good find!)

We were here formed up ready for the journey. The truck I was to drive was loaded with the kit bags, which gave me the amusing thought that they won’t leave me behind as I have all their kit. A few miles up the road the old saying ‘never a true word spoken in jest’ came to mind; the Chev came to a halt and so did the convoy. (I don’t know who drove it from No. 5, but there had been no mention of any trouble with it on the journey). A tow rope hooked me up to the truck in front and I was towed until an area of firm sand was found so that we could get off the road. With some assistance we found that the ignition had failed due to the points burning. Having cleaned them up we were on our way again, but I knew this could have been caused by a faulty condenser and just hoped we would make the rest of the journey before the points blacked up again.

Arriving at El-Firdan without further trouble we were directed to our living accommodation. This time we would be in rows of tents on soft sand and although these tents were on ground level, inside we found we were able to stand up. Under each tent, the sand had been dug out and a wall of sandbags held the sand back. There were steps to get down onto the stone slab floor upon which there were three beds per tent. I soon realized that this floor would have to be constantly swept of sand – all so different from our accommodation back at No. 5!

It was decided to take the Chev to the tents where the lads could collect their kit straight from the truck; but it did not occur to me at the time that the heavy truck could have caused those tent walls to collapse – luckily no one saw us. To make matters worse I accidentally caught one of the lighting boxes just sticking out of the sand and was hoping none of the lines would be without lights that night.

At El-Firdan the engineering officer was a F/L (Maltese) in charge of the workshops. Two days after our arrival he invited us to meet him in the NAAFI where he bought all the beer, at the same time asking questions such as what we thought of the place and what improvements could be made in the workshops etc. Much to our surprise some of these were implemented.

Now here at No. 10, instead of Arab fitters, we had German POW’s in the workshops. They had their own separate area on the camp independent of us; they had their own cookhouse, barbers, tailors, medical unit etc. They also had a business going in the form of a souvenir shop made from a huge wooden packing case with a door and window which was parked in our tent lines. In this shop they were selling cigarette cases with covers depicting the Taj-Mahal etc. made from duralumin with toothbrush handles as material for the jewel inserts, polished wooden cantilever sewing boxes among many other things (the materials taken from the U/S (unserviceable) aircraft in the compounds). There were ‘Africa Corps Hats’ on sale in the shop, made from kit bag canvas. We could take in a photograph of a girl friend or wife to them and they had an artist who would paint a portrait from it. The POW’s were well organized, they even made sets of their own clothes and they used to get local women in through the back of the camp (they took pleasure showing us the photographs they had taken of them). All these men were skilled in trades – blacksmiths, instrument makers, fabric craftsmen,, sign writers etc. We had the benefit of getting our watches etc repaired by them. There was an Armenian on the camp selling watches; I took three he was offering along to the instrument section, the POW’s took the backs off examined them and I bought the recommended one for £8

On the compounds, as well as vehicles and aircraft, there was what could be classed as complete aerodromes on wheels: wireless vans, airfield control vans, mobile kitchens, mobile workshops, stores vehicles (the bins still labeled with parts for Spitfires, Hurricanes etc), fuel bowsers, water tankers, the sixty foot ‘Queen Mary’ aircraft transporters, even mobile dental surgeries; everything needed for an operational airfield.

We had to do gate guard and each night there were always seven men detailed for this duty; but only six were needed. The smartest man was picked out as ‘Stick Man’ and excused. There was more discipline and ‘bull’ here than there had been at No.5. Among other things there were regular tent inspections and for this our webbing harness had to be displayed in a certain pattern on the bed with brasses polished. One morning, having been ‘stick man’ the night before, I thought my brass was polished enough but when I returned from the workshops I found my webbing scattered all over the bed, so I went to see the orderly sergeant, who happened to be one of the No. 5 NCOs. I asked him what had happened and he told me that the officer considered they had not been polished. I told him that I had been ‘stick man’ the night before and his reply - "stick man I would have given you the stick" and with a grin I departed.

Abe was not so lucky, he got caught over something that did not comply with the rules and was put on a charge that awarded a spell of "jankers". For this he had to parade in ‘best blue’ wearing webbing and large pack at six o’clock for inspection, then change into ‘fatigues’ to work in the cook house until ten o’clock, clean up and then report again in ‘best blue’, pack etc for inspection again. The other two lads in his tent helped him with his webbing, brasses etc to make sure he would pass.

Abe on jankers, in his 'best blues' and carrying a large pack

El-Firdan translated would mean "The Crossing" and had Biblical connections, so we were told. At the rear of the camp across the open desert we could see the upper parts of the ships as they passed along the Suez Canal – this gave the illusion that they we traveling through the desert. Although the gate was guarded, the desert at the rear of the camp was open and to cover this area there was a roving guard. This was in the form of Station Police in two jeeps with mounted searchlights and Bren guns. A sighting at night would see them charging off into the darkness, the a burst of gunfire and on some occasions a fleeing Arab would be brought back with a bullet in his rear.

Not long after arrival I started having trouble with a tooth, so reporting sick, I found myself with five other lads in the back of a 3 ton truck being driven south along the Treaty Road to an RAF station that had a dentist. We were in turn sent in to see him. Pointing to the tooth he immediately injected my gum and I was told to go outside and wait until called, I think the dentist was a Squadron Leader (both doctors and dentists had high ranks). I joined the others outside round the back of the building, then when all our faces were numb; in turn we were called back in. When it was my turn he started tugging at my tooth saying it should have been seen earlier as it was difficult to get a grip on it. Then we were on our journey back with lads hanging over the tail board spitting blood all the way.

There were occasions when the German POWs were missing the sandwiches they brought in with them for their lunch. After a few such incidents they took action by putting a strong laxative in with the fillings with the result that some of the Arab labourers, that were employed to clean the hangers, went missing. There was also a group of these employed to empty the camp toilets. This consisted of a gang with a high chassis Thorneycroft lorry loaded with large metal bins. This work carried on daily without incident until the day we were all formed up on the Parade Ground in our ceremonial uniforms for a visit by the ‘Top Brass’ and this Thorneycroft, with the cleaners sitting up on the back among full bins sloshing over, drove right across the Parade Ground.

A trip to Cairo was organized and as we were speeding along the bumpy Cairo road the driver ran into a pack of ‘Piards’ but just sped on, I presume he did not intend to go off the road and hit soft sand. In Cairo we transferred to a waiting Egyptian coach for a sight-seeing tour of the city which took in the many Mosques etc. During this journey the coach was pelted with lumps of mud – I think it was mud! It was in my mind that they knew we were British forces and that although they liked our money, they did not like us. After visiting the Cairo Museum to see all the antiquities from the Pyramids we then went on to see the Pyramids.

|

|

Being taken along the passages inside I was surprised to see that electric light had been installed, but it would have been difficult in there without it! Back out we were then taken by the Dragoman (Guide) down under the Sphinx to see the temple below.

We made regular visits to Ismailia and on one occasion a 15 cwt truck and driver was hired for a trip to a local ATS camp where we had to sign for an equal number of girls to take to a place in Ismailia that had a dance floor with chairs and a windup gramophone for a dance. On arrival the lads paired off for the evening, but I, the shortest, was left with the tallest, so I spent the evening breathing on the top button of her tunic. At the end of the evening we had to return the girls to their camp and have them signed back in.

On one visit to Ismailia I bought myself a sports jacket, trousers and tie in order to go out in civvies once in a while. Wearing civvies did not save us from being pestered in the streets and there were times when we had to go in to shops just to get away from the beggars and street sellers (I sometimes wondered if they work with the shop keepers to drive us into the shops!). The shopkeepers made out to look as though they were chasing them off and as for the Egyptian police (armed with their ancient single shot rifles) they were useless and always turned the other way. Ismailia was our nearest town and one of the favourite places for forces to go was the Blue Kettle Club which was open to all ranks. We always called in there for tea and something to eat.

|

Me, in winter khaki |

My new civvy outfit |

|

The Chapatti seller in Ismailia |

Street barber in Ismailia |

In time the German POWs were allowed out of camp to within a distance of five miles. Returning from a duty run one night we were waved down by one of them with a nasty slash in his shoulder – he had been attacked and robbed of his watch. We got him on board and made for the nearest military hospital.

I was elected to represent the workshops on the station committee and before each meeting there was the task of going all round to hear of any suggestions or complaints that should be passed on to those responsible. One request that I was asked to bring up at every meeting was for a swimming pool which I was duty bound to put to the CO but in the desert!? It never got anywhere. We did have a swimming Gala but this was held at Moascar Garrison. They also had a sports ground with lush green grass and whenever we went to Moascar, I would go to look at this grass, in a land of sand; this was a reminder of home. On a visit there I saw a huge lizard asleep under the hedge; I decided he would only be there because of the grass and the constant watering.

The church at El-Firdan built by POWs from packing cases

I was told that the German POWs at El-Firdan were to be thanked for the church, which they had made from packing cases. Some of these cases were huge; I was told that the newly arrived long wheel back Thorneycroft Coles Crane had been sent out in one. It had two cracked brake drums when it arrived and now faced with a long wait for replacement drums to be sent out, the faulty drums were removed and we drove it around without them. There were many uses made of packing cases, often the smaller wooden cases were used by officers returning home (one was opened to find one of the Harley Davidson motor bikes inside!).

|

The new Thorneycroft LWB Coles Crane |

3 Ton Bedford QL - with no brakes! |

There were always vehicles held up for spares such as the two Studebaker artic tractor units. They had been standing there in the workshops before we arrived; waiting for parts from America which could have been made in our machine shop – this was suggested and agreed as a good idea but I never knew if it was implemented. I collected a Bedford QL from the rows of vehicles awaiting repair. Although not on the worksheet, it had no brakes, so to stop it I had to steer it between the rows and miss hitting any, until the soft sand brought it to a standstill.

One of the POWs in our group was called Booe which I thought might translate into boy because he was so young. They told me that he was only sixteen when he was sent out here. I think most of the POWs probably considered that while working they were not aware of the time pending their return home and as each vehicle was ready another was brought in from the compounds.

There was the occasion when we had a new arrival that seemed to know his way around, could speak the language and was known to some of the Arab workers. We found out that he had been stationed at El-Firdan before, went home, got demobbed and started a betting shop, but got so heavily in debt, that to get away he rejoined and was sent back to his old station.

There was a tragedy during the time at El Firdan. One of the stores suffered many attempts of being broken into and in a rather isolated position and containing blankets etc, it was the practice for one of the store personnel to be billeted in there, until one morning he was found dead with his rifle beside him. We heard no more after that; except that the Carpenter’s shop had the job of making a coffin.

After our stone buildings at No. 5, we got accustomed to being in tents, until one night, returning from the cinema we were greeted by one of the biggest spiders we had ever seen. Once caught, we took it across to the hospital to be identified and were told it was a camel spider.

It was in that hospital that I had to spend a week living on just Assis (Grape fruit juice) to clear a dose of dysentery (I suspected the flies on the tea cups at the tea kiosk by the canal). It was in the night I woke suddenly with the need to dash to the toilet which meant a trip in the darkness though the tent lines as the nearest were the other side of the tented area. (Placed at intervals in the tent lines were buckets surrounded by a waist high sackcloth enclosure for convenience of the lads that had drunk large amounts of NAAFI beer). But for a more serious reason there was this journey, plodding over about three hundred yards or more of soft sand. No sooner was I back in the tent than I was off again and the trouble with such a situation there was that toilet paper was never supplied. (At Weeton rolls were put in the toilets on Saturday morning ready for the COs inspection, but removed afterwards – anyone quick enough would gain one for themselvers.) My answer to this problem was post from home; each week my mother would send me the Daily Mirror which was the week’s editions clipped together in an outer cover of yellow paper, which I saved for such a purpose. (There was the remark often made that the RAF toilet paper issue was five sheets a day but this may have been just a story.) After a night of these trips I put my towel and toilet things in my small pack, as per regulations for reporting sick and made my way to the sick quarters, which was only the far side of the tent lines.

Arriving there I was given a bed and a bed pan and was visited by the Medical Officer who decided I has a dose of dysentery and gave instructions that I was to have a jug of Assis and nothing else. Later, from my bed I could see through to a small room where the MO with two spatulas was going through the contents of my bed pan – to confirm his diagnosis? I lay in that bed, for five days watching people passing through, with just a jug of Assis beside me, until it was announced I was fit to return to duties, from then on I was very wary of flies!

As time passed there began speculation about going home. There were already a number of the older men leaving; one, a sergeant from South Africa, was going home without having to go to the U.K. There were often discussions among the men about how long they had been out there and there was one who always gave the same answer – that he loaned the shovel to Ferdinand de Lesseps when he was digging the Suez Canal! There was a group of lads, who when their number came up were not going home; instead they planned to go to Australia on a scheme that was being offered. This would mean joining a ship at Port Said that was destined for that country, as many of the ships were that sailed down the Canal. Many of us had been called up under the War Time Act titled "Duration of the Present Emergency" and given a demob number, but we found that much depended on the needs of our trade – fire fighters etc got away as expected, but fitters and mechanics were often held back. The names of some of the lads in our hangar were on the notice board, they held the usual ‘Boat Party’ in the NAAFI and next morning with their kit, were on board a QL ready for Port Said only to be told they had been held back. One of the lads, a Winfield-Chislet, had been clipping off a small piece of his tie daily as a ‘Count down’. He had to be on the next Clothing Parade with a reason for his action, rubbing ties on the wall to hasten wear often resulted in getting a new one – but this?

In anticipation of my number coming up, I had asked friends in the Fabric shop to make me an extra large kit bag in order to take home my many acquirements over the time in the Middle East. They even stitched an extra handle at the bottom end ready for assistance in view of the weight! I also had a large metal trunk made for me by the blacksmiths with a view to taking home some of the things that were left in the wireless trucks in the compounds at No. 5 but by now I had made the decision not to bother, but as we were allowed a "deep sea" item I decided the trunk could be useful back home. It would follow me some weeks later, but as there would be nothing of importance in it, that would not matter.

The day came to attend for the usual discharge medical at our little hospital, then followed a meeting with CO who asked if I would consider staying on, pointing out all the benefits if I signed on. I thanked him, saying that my old job was waiting for me.

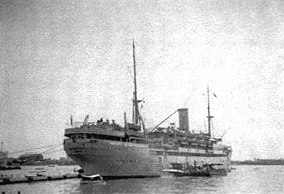

Two days later a little group of us from No. 5/10 were at Port Said boarding the Empire Windrush, at the same time some of the POWs were boarding another boat to take them home.

|

My happy demob facw |

My boat home - the Empire Windrush |

News came later that not all the German POWs went home from Egypt at that time. At Shallufa there were about 100-150 left behind. Their homes were in the Russian Zone of Germany and they weren’t sent home because of the risk to their lives. They stayed on working in the messes, MT yard, instrument repair shop and various other sections. They also took part in guard duties; RAF personnel had rifles and the POWs carried wooden clubs. Later a number of them found homes in Turkey and the RAF was the worse for their absence. This would have been the same situation at E Firdan and other stations throughout the Canal Zone.

We sailed on time, but on the second day out one of the engines broke down; so there we were with one engine hugging the coast of North Africa. On deck entertainment was being provided by anyone that had anything to offer; from mouth organs to wrestling. The wrestling demonstrations were provided by two ‘stowaways’ that had been found on the ship, they had deserted from the Regiment of Lancers in Egypt. For their performance a large canvas tarpaulin had been laid out on deck but it had been put over two large iron hatch fitting rings with the consequence that one of the lads landed on these and broke his shoulder.

We sailed out through the Straits of Gibraltar and struggling through the rough seas of the Bay of Biscay we were fed on tripe – the first and only time I have eaten it. At the start of the journey some of my friends had been singled out to work below in the galley for the whole trip!

After ten days we reached Liverpool and we were surprised to see the girls waiting on the dockside looking different from when we left – it was the ‘New Look Fashion’ that had come in while we were away.

The first off were the two prisoners escorted by two ‘Red Caps’, then married families and the service women. Finally it was our turn and picking up my kit bag on the dockside I was glad of the extra handle they had put on in the fabric shop. With the heavy wooden workbox for my mother, the bottle of Cyprus Sherry encased in a wooden box (for safe transit – courtesy of the carpenters shop at No. 5) as well as gifts for my sisters, it was so heavy that I had to drag it along. The canvas was beginning to wear away through rubbing the ground when one of the lads kindly took hold of the extra handle. Passing through customs the officer said "What have you got in there – the ship’s anchor?" Waiting outside was a 10 ton Leyland Hippo and with all loaded we were transported to RAF Warton for demob.

At Warton we went through the Demob procedures – handing in our boots and kit. But keeping our ‘Best Blue and best KD’, my old faithful knife, fork and spoon that had been with me since Padgate, had to be thrown into a large metal dustbin that was already full and I also said goodbye to the mug, another old friend. My greatest regret was not being allowed to keep my great coat; it was a perfect fit and very warm but before leaving El Firdan it was announced that all those returning to the U.K, were to report to the clothing store with our great coats where we were ordered to "throw them over the head of the WAAF otherwise we would not be going home". Minus my coat I was hoping it would not be as cold in the U.K. as it was when we left. In the next section of the store we were issued with a ‘Demob suit’, a black/grey mixture that would certainly need a tailor to get it to be any near my fit. I was also given a trilby hat which was much too small, but was told I would have to take it as that was all there was and everyone had to leave with a hat!

Now with pay, a 10 day demob pass and travel warrant, I was on the train home arriving there at five o’clock in the morning and having to wake my mother up to let me in, but I did not see my father or sisters until they got up later.

This is Alan Lester, our camp cartoonist with some of the cartoons he did of me.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|  |

|

| |