By Peter Vaux

!A typed version of this story, written in the‘90’s by former

Canal Zoner, Peter Vaux (who sadly died in 2003) was discovered in our Archives

in 2012.. It was never published in the Newsletter back in the 90's as it

was considered "too long for publication", even though it tells

a fantastic story of how life was back in 1940's Britain. It really is a "Must

Read Story" and should be shared with everyone. It was featured in our

Newsletter in parts over a few Issues in 2016/2017, when we were informed

that a paperback version was now available. As we hold an orignal typed version,

no copyright has been infringed upon)

This is the story of Convoy WS 5A which, having embarked 4th Royal Tank Regiment under Lieut Colonel Walter O’Carroll DSO and 4th Royal New Zealand Artillery Regiment under Lieut Colonel Fraiser, sailed from Liverpool bound for Port Tewfik, Suez, on the 18th December 1940.

The entry of Italy into the war had been expected by Churchill for, in addition to bellicose speeches by Mussolini, a very large build-up of forces was becoming apparent in Libya, posing a severe threat to Egypt and the Suez Canal, life-line of the British Empire. Churchill now faced a crucial dilemma for it was also clear that Germany might soon attempt a sea-borne invasion of Britain preceded by an aerial onslaught. Resources on the ground available to confront these two threats, after the losses in France, were meager in both cases. With courage and a steady nerve, the Prime Minister ordered that reinforcements, especially armour, should be dispatched to the Middle East as they became available and could be spared from home defence. From August 1940 an increasing number of convoys carrying troops and equipment were to sail for the Middle East, mostly by way of the Cape of Good Hope.

These convoys, which were loaded and assembled with great urgency, were known as “Winston’s Specials” and were given the prefix “WS”.

Invasion Stand-by

During September convoys carried 2nd & 9th Royal Tank

Regiments as well as the 3rd Hussars round the Cape of Good Hope to Suez and

3rd & 5th RTR were both soon to follow. With the 1st & 6th RTR already

facing the enemy in the desert we of 4 RTR began to feel rather out of things.

In June 1940, returning very battered from France, we had assembled on Tweseldown

Racecourse, near Aldershot, where we received reinforcements in officers and

men and were made up to strength in new Mk 11 Matildas and Mk V1C Light Tanks.

At the end of July we moved to our operational area in Sussex, with the headquarters

in East Grinstead and squadrons in surrounding villages and on large estates.

Each squadron was provided with a tank train, complete with mobile ramp and

crew accommodation, with which they exercised regularly, by day and night,

ready to stream to the scene of any German landing on the coast.

As in France the previous September to May, I again had the Reconnaissance Officer’s task of reconnoitering numerous routes for counter attack, noting tank obstacles and other hazards. But first I was required to find, requisition and allot billets, buildings for workshops, stores and offices, and concealed areas for tanks and other vehicles. The task was even more distasteful than it had been in France, where at least I had the support and authority of Monsieur Le Maire who himself inflicted the requisition forms upon the unfortunate householders selected by me, whose protests I would pretend not to understand. Now I had at my side only a local police constable – who tended to feel more sympathy for the victims than for me – my slender authority no more than a handful of ready-signed requisition forms and a solitary pip on each shoulder. Even when a second was added it made little difference. Moreover, I could understand the heated protests and abuse the landlords directed at me only too well.

However, the job got done and we all engaged in intense planning and training during a period of frequent invasion scares. Meanwhile we succoured baled-out RAF pilots and the light tanks gathered in shot-down enemy aircrew as the Battle of Britain raged overhead. That battle having been won by October, and Hitler’s invasion barges in the French channel ports destroyed by the RAF, there was some relaxation of anti-invasion readiness and short periods of leave were allowed.

Action at Last

In November, B Squadron, newly issued with tropical clothing

and a Scammell tank transporter, abruptly departed for an unknown destination,

taking away our REME officer and many of his fitters with them. We were not

to see them again for over six months. They were embarking upon an extraordinary

journey which would take them over 800 miles on their tracks through Egypt

and the Sudan to Eritrea, engaging with the 4th Indian Division in a harsh

but successful campaign through the mountains against a larger and well prepared

Italian force. The Italians defeated, the squadron reached the Rea Sea at

Massawa, where they embarked once more for Suez, bringing 15 of the 18 Matilda

tanks with them, all in running order if in dire need of overhaul. That is

a rather thrilling story which has yet to be fully told.

In early December, while on a few days leave in Devon, I was startled to receive a telegram worded “Treat present leave as embarkation”. A compassionate thought by Captain Bob Ramsay, the Adjutant. Back in East Grinstead I found the regiment in a state of controlled turmoil. Everybody was being inoculated and issued with tropical clothing, which the civilian population was not supposed to see – though people kept asking when we would be leaving for Egypt – while our tanks were being prepared for a sea voyage, ready for loading on trains for Avonmouth docks together with skeleton crews and the whole of the unit transport. On the 12th I was ordered to assemble an advance party of one other officer and a number of NCOs, cooks and orderlies to be provided by A and C squadrons and the headquarters departments, to make sure that we all had our personal arms, kit and bedding and to proceed to Liverpool by train. In those day East Grinstead still had a railway station. The main body would leave on Sunday, 15 December – everything always happened to us on a Sunday.

On the 13th December, after a tiresome train journey, my small party arrived at Liverpool’s Lime Street Station in the black-out, to find an air raid in progress. A helpful Railway Transport Officer ushered us into some subterranean shelter until the 'All Clear' sounded and then directed us towards the Transit Camp some 250 yards down the street, to which we now groped our way, staggering under the weight of our considerable belongings. Arriving rather disheveled and very hungry we found the Transit Camp to be an old and shabby five storey office building, whose owners must have been delighted to see requisitioned. A somewhat disagreeable Captain, old enough to be the grandfather of all of us and sporting antique medals, but who was apparently in charge, informed us that we were too late for a meal, that our accommodation was on the top floor where there were beds but no bedding and that we were confined to camp until 7 am when we were to report to him, breakfasted and ready to leave. As we climbed the narrow stairs we passed the kitchens where, with a wink, a jovial cook provided us with soup, sandwiches and tea.

In the morning I duly reported to the OC Transit

Camp who, having checked who we were and consulted a list, stated: “You

are for London”

“No”, I replied, “I don’t know exactly where we are

going, but it is not London”

“The CITY of London!” he snapped “Number

5 Dock, Gate E”

“Right,” I said, “where do we get transport?”

“Transport!” he exclaimed. “Do you think this is the Ritz?

You take the tram from over the road” I considered saying that I had

no tram tickets, but thought better of it and bought them myself. I half expected

the conductress not to let us board when she saw our laden and encumbered

state, but she relented at the sight of our black berets for, thanks to the

Territorial Army, the Royal Tank Regiment was popular in Liverpool.

The “City of London”

Duly alighting at Gate E, we staggered through it on to No.

5 Dock, tripping over railway lines as we went. There, looming alongside,

was indeed the City of London. A conventional, old-fashioned but still handsome

single funneled City Line cargo steamship of 10,600 tons displacement, she

had a long white superstructure amidship suggesting considerable passenger

accommodation, while her derricks indicated five holds, three forward and

two aft. From these holds and both decks came the sound of many carpenters

working feverishly. One of the derricks was busy hoisting aboard planks of

timber and other building materials.

As we gazed upon our future home we were approached by a young Royal Engineers captain wearing a white armband, the Embarkation Staff Officer.

“You must be 4 RTR” he stated briskly. “The advance party of 4 New Zealand Field Artillery Regiment is already aboard. The train with their main body is due alongside here at 6 am the day after tomorrow, the 16th, and yours at 7 – air raids permitting. There are some stores for you here on the dockside – tank tracks, packing cases and the like. Stevedores will load these with their crane as they are cargo, but if you put your personal kit on that cargo-net the crew can sling it aboard with a derrick as it counts as baggage. Now come on board; you’ve all got a lot to do before the trains arrive.”

I was glad to see those stores as they were essential spares which had arrived too late to go on the ship with the tanks, but the distinction between cargo and baggage (even when it was on a “cargo-net) would become clear only later.

At the head of the gangway we were met by a young two-ringed Merchant Navy officer who was introduced as the Troops Officer. “Troops” was to become an essential and valuable link between the ships staff and the military units, magically resolving many of the difficulties which were soon to confront us all. He now conducted us round the ship where workmen were attempting against time to finish off her conversion to a troopship with accommodation for 1400 all ranks. “Troops” explained that one hold had been retained for a small amount of cargo and the other four holds were being turned into troop-decks by the installation of flooring, lighting, plumbing and stairways. Rows of tables and forms were being fixed to the floors with above them numbered beams bearing hooks for slinging hammocks and clothing. In a corner of each troop-deck, mixed up with the carpenters’ tools and materials, was a great pile of hammocks and kapok life jackets.

The two after holds had been assigned to the New Zealanders, who were already at work trying to allot and mark out groups of tables for sections, troops and batteries, distributing the hammocks and life jackets among them. We were to do the same in the two forward holds for our own regiment. Each regiment would also have to cater for some minor units and a large number of assorted individual reinforcements of all ranks. Amidships were dining and general saloons and a small library. There had originally been cabins for 231 passengers but some of these had been taken for administration and the remainder had had extra bunks fitted, as space for officers and senior ranks would be tight. “Troops” took over my nominal roll of officers, saying with a wink that he himself would allot cabins to all officers, making due allowance for rank, as it might save me a load of trouble. It was apparent that he had done this job before.

On the two well-decks wooden structures had been erected and were now being fitted out as troops galleys. There were also on each deck several large fresh water tanks. Aft, under the poop-deck, were the ship’s hospital and orderly room, to both of which we must allot staff. Here I found the Adjutant of the New Zealand Artillery Regiment, Captain Bill Thornton, who informed me that he was to be Ships Adjutant and I was to be his Assistant. I enquired what sort of work we would be doing and he grinned, saying that I might make a start on the Ships Standing Orders, so I changed the subject. The ship could not have been in better hands, for Bill Thornton was not only already seasoned by a voyage in a troopship from one side of the world to the other but was the caliber of officer who was to become Lieut General Sir William Thornton, Chief of Staff of the NZ Armed Forces, and still later Her New Zealand Majesty’s Ambassador to Thailand. There were also, we were to discover, a Ships OC Troops, an elderly and rather wizened British Lieut Colonel who, except at meal-times, seldom appeared until we reached warm waters when, dressed only in a pair of shorts, he took station all day in a deck chair on the upper bridge, in solitude save for a book and two anti-aircraft Bren gunners. He never entered the ship’s orderly room nor did he worry us at all, and he eventually turned dark mahogany. Mean-while, he laid down that 4 RTR were to man the anti-aircraft defences during daylight. These positions consisted of four Bren guns mounted in concrete lined posts on the corners of the superstructure and were to prove very exposed and bitterly cold in bad weather.

Next day, just before dark, I went down on to the quay to check exactly where the trains would come in next morning. It was annoying to see our store still lying there, a group of dockers lounging beside their crane smoking. I asked the foreman when he would be loading these things but he turned away, saying something about have no time. At 4:30 I remarked to the Embarkation Staff Officer that as we had enough manpower to load the stuff ourselves with the help of the ship’s derricks I would speak to “Troops” about doing so. “For God’s sake don’t do that!” he exclaimed “you’ll have the whole docks out on strike if a soldier touches cargo”. Later, the foreman approached me and asked the time, I told him it was one minute past five. “Right lads,” he called “let’s get on with this lot, we’re on double time now.”

So much for the trades union war effort, I thought. Shortly afterwards all the carpenters trooped ashore, their work still far from complete. Our cooks could at least now get to work in one of the galleys, but the other had not yet been finished. We were most unhappy about this for clearly there was going to be great difficulty with the messing.

In the event there was no air raid that night but next morning the trains were late all the same. The regiment detrained at 8 am and fell in on the quay tired, hungry and rather fractious. We shepherded them in the morning darkness up the gangways, enjoining them to avoid ropes and hatch coamings and so down to the brightly lit troop decks and a hot meal. Everything smelt of newly sawn wood. We left them struggling with their hammocks, old India hands now in their element. The officers proved rather more tricky, the companion ways being narrow, the cabins small and not all being entirely satisfied with their cabin-mates. I was happy to disclaim responsibility, blaming the Troops Officer. Some wanted to go down to see how their soldiers were faring but we persuaded them to wait till later, there was enough chaos down there, with all those hammocks and life jackets.

The remainder of that day and the next, 17th December, was spent settling into the ship which really was not ready to accept passengers. This was in no way the fault of the ships company nor of City Line but was simply a consequence of the terrific rush in which everything was having to be done. The messing arrangements were very bad as, there still being only one galley, half of the men had to go over open decks from one end of the ship to the other to collect their food. Tea had to be made in 40 gallon boilers which never seemed to get properly hot. Colonel O’Carroll was far from pleased and asked the OC Troops (Lieut Colonel Line) to call an immediate conference together with the New Zealand CO (Lieut Colonel Fraiser) and the Troops Officer to discuss the messing arrangements. By evening much had been done to improve matters and soon both galleys would become operational. We tried out our boat stations for the first time and began to get used to carrying our life jackets wherever we went but, though nothing was ever said even in private, we all knew in our hearts that there were nothing like enough boats for everyone and that in the event of a disaster most of us would be floating in those life jackets and hoping for the best.

We sailed at 0410 hrs next morning, the 18th,

and as dawn broke over the mouth of the Mersey the convoy and its destroyer

escorts were beginning to form up, the great stone birds on the Liver Building

now becoming visible. Soon they disappeared behind us and there must have

been few who did not wonder whether they would ever see them or the shores

of Britain again. Sadly, many would not. As the coasts of England and Wales

faded into the mist and we passed through the North Channel between the mountains

of Ulster and Scotland there was somewhere for everyone to sigh for. So we

steamed out into the Atlantic, past the deserted Isles of St. Kilda and the

tall lonely granite shape of Rockall, heading west until it was thought that

we might be clear of U-boats and could turn south. For the first time we heard

at dusk the rather eerie call on the Tannoy public address system to “Darken

Ship – Darken Ship” after which no lights or cigarettes must be

visible from outside. That was the time when all rubbish had to be thrown

overboard at once, so that no trail would be left for submarines to find and

follow.

PART II

The North Atlantic

Twenty four hours later we were well out to sea, the passengers

now settling into ship-board routine. The second galley had been brought into

use so that there could be regular times for meals and for opening bars and

canteens, rosters for duties and fatigues (there seemed plenty of these) had

been produced and even the drill for rolling up those hammocks and lashing

them neatly to the overhead beams had been mastered. At night these last swung

so closely together as to touch and sway in unison with the motion of the

ship so that the orderly officer on his nightly round had to duck beneath

them, in rough weather running the gauntlet of any occupants who might suddenly

become unwell. The radio cabin beneath the bridge, forbidden to transmit,

could at least receive Reuter’s news, which was taken down and issued

as a news-sheet which was to develop into a regular ships newspaper, complete

with articles and puzzles, edited by the Chief Clerk. Lance Corporal Cowper

having found a store of records and a record player appointed himself ship’s

DJ on the public address system, and read us two bulletins a day as the news

of General Wavell’s victories against the Italians became ever more

exciting.

I had indeed found myself responsible for drafting Ships Standing Orders, not all that difficult as there was an excellent War Office example to crib from. Having seen this old cargo liner only a few days before being hastily transformed into a fully fledged and working troopship, complete with all the necessary supplies, equipment and documents, I reflected on what a remarkable feat of organization this really was, despite the immediate shortcomings, considering that even six months ago nobody had dreamed of sending armadas of such ships thousands of miles around the world.

The two Adjutants and the regimental training officers were soon busy devising programmes of lectures, classes and exercises to keep everyone fit and alert. Amongst the officers traveling independently was Major Guy Prendergast, RTR, who was going out to command the Long Range Desert Group. A notable Arabist and desert explorer he was roped in to give Arabic lessons to the officers and to teach desert navigation. Many other officers, especially amount those with Emergency Commissions, had interesting experiences to relate and lessons to impart to all ranks.

The ships officers willingly entered into the series of lectures with tales of sea-going adventure. The Master, Captain Longstaff, had served in the Great War and had already survived a torpedoing as had Mr. Macauley, the Chief Engineer, who was in the liner City of Benares when she was torpedoed in the Atlantic in the first fortnight of the present war, with the loss of hundreds of evacuee children. He never spoke of this and was said to suffer constant nightmares. Officers and senior ranks were taken on tours of the ship in order to familarise them with all aspects of her geography, in case of emergency.

The City of London was built by Workman, Clark & Co, Belfast, in 1906, six years after City Line was absorbed into the Ellerman Group. She was 491 feet long and was fast, having a designed speed of 15 knots, but she had reached 17 knots on trials. Her pride was her engines, being single screw, four cylinder quadruple expansion, 215 psi, 660 NHP with two double and two single ended coat-fired boilers. The engineers claimed that she had the longest piston-throw of any reciprocal engines afloat and certainly we were duly impressed when we visited the engine room. In 1909, whilst on the Bombay service, she took the Bombay-London record in 18 days and 19 hours. In 1916 she was requisitioned and converted at Calcutta into a Armed Merchant Cruiser with eight six inch guns and two six pounders, serving in the Far East. Refurbished by her builders in 1919 she re-entered the service to India, in 1923 recording another record time of 23 days from Calcutta to Liverpool. She was on the South African run at the time of her second requisitioning in 1939.

We now had time to look around at the twenty very assorted ship of Convoy WS 5A, which were to carry over 30,000 troops and much valuable war material round the Cape of Good Hope to Egypt. These were arranged in four columns of five. We were at the head of the left column and on our starboard was the Shaw Savil liner Tamaroa carrying the Commodore, a Royal Navy Captain in charge of the convoy. She also carried a contingent of QA nurses so that the diligent binoculars trained upon her were not only watching for orders from the Commodore. Further over was the beautiful Reina del Pacigico – also carrying nurses and ATS girls. Other ships whose names come to mind were the Empire Trooper, the Belgian Elizabethville, our sisters the City of Canterbury and City of Derby, Blue Funnel’s Menclaus. And PSNC’s Orbita. The last two were to cause us trouble later on. Elizabethville was a large, black and forbidding looking Belgian coal burning freighter stationed directly astern to us. From time to time she would emit clouds of black smoke prompting furious reminders by Aldis signal lamp from the Commodore that she endangered us all, the black clouds being visible to U-boats far beyond the horizon. Many of the ships burnt coat, but few behaved like that. Another characteristic was her inability to maintain steadily the precise speed of the convoy. Every day or two we would see her falling far behind, to the inconvenience of the three ships astern of her in the column. At other times she would rush up quite close to ourselves, her bow appearing to rear above our stern or creep up alongside, but she was not the only ship liable to do this, especially in rough weather.

At night of course there were no lights of any kind to be seen anywhere in the convoy and it really was essential for all ships to maintain the same course and speed. The convoy changed direction in zig-zag fashion every few hours night and day. At a signal from the Commodore of one or two blasts of his siren all ships would swing so many degrees to starboard or port as defined in schedules held by each Captain with his sealed orders. This very tricky manoeuvre was unfamiliar to merchant seamen, but there could be no mistakes.

On either flank of the convoy could be seen the lean grey shapes of our escorting destroyers and frigates, their numbers varying from day to day as they were relieved or diverted elsewhere. Sometimes one would dash off on her own in pursuit of some real or imagined U-boat and we would hope for a bit of excitement. One afternoon our alarm bells sounded and we all mustered by our boats from where we could see that other ships were doing likewise. Three depth charges were dropped by a destroyer and a gun was fired, it being said that the foaming wake of a torpedo had been seen passing harmlessly through the convoy. The movements of our escorts were always interesting. In rough seas their low hulls would disappear in clouds of spray while green water sometimes rolled over their decks. We marveled at the discomfort the crews must endure, battened down and being thrown about, and were filled with admiration and gratitude.

As our course took us far out into the Atlantic the wind increased in strength and the sea became much rougher, so that many people, including myself, became very seasick. Dr Charles Anderson, our Medical Officer and one of my cabin mates, sought to find a cure. He injected me with a drug intended to immobilize the ‘semi-circular canals’ in my head which he claimed controlled the sense of balance and were the cause of nausea. This was successful in that I no longer felt ill but, deprived of a sense of balance, could not stand upright and kept falling over, unable even in daylight to tell which way up I was. Thus failed an experiment which had promised great benefit to mankind.

Soon, as the winter gales reached hurricane force, the convoy had to slow down and the ships spread out, the zig-zags being temporarily suspended. Nobody was allowed on deck but, peering through the portholes, we could see other ships swaying and pitching, rearing up over white-topped rollers, sometimes lost to sight in their own spray and the spume blown from the wave-tops.

One night we heard a great crash on the forward deck and the ship shuddered. We feared that the hatch covers, beneath which were the troop-decks, might be damaged – but they held firm. In the morning, however, we found that one of our galleys with everything in it, but luckily unoccupied, had been carried overboard by huge waves. Thereafter our catering capacity was reduced by 50 per cent. In fact, only little use could be made of those improvised galleys on deck during such weather but, as conditions below were indescribable, there was little demand for cooked food anyway. The troops galleys were manned by regimental cooks who did their best with the rations supplied from the ships cold rooms and stores, but quite soon items such as fresh meat and vegetables gave way to tinned and dried supplies, but the ship produced newly-baked bread. The loss of a galley was dealt with by staggering meal-times and by bringing the officers galley into the equation.

Sailing further south the gales abated but one dark night, as we all slept at about 3 am, the ship’s siren gave two long blasts and she rolled violently, throwing many people out of their bunks and hammocks. Simultaneously we felt a heavy and prolonged blow which shook the vessel from end to end and the alarm bells jangled loudly in the silent companion-ways and passages. Never before had boat stations been reached with such speed nor life jackets so firmly gripped. As those of us on the starboard side reached the deck we could see almost alongside the great bulk of the Menelaus, her quarter with broken and dangling hand-rails overhanging ours. Slowing the two ships swung apart and our engines, which had eased, resumed their regular beat. The Orbita and the Elizabethville also were in unusual positions and all four ships were very close together. We remained on deck, shivering in our underclothes and bare feet for an hour or so, while the ship was thoroughly checked, before being allowed below. Next morning “Troops” told us what had happened for he had been on watch at the time. We had been engaged in a scheduled turn to starboard when the Menelaus, apparently failing to confirm, surged towards us. “Troops”, who was fully alert, judged that her bow would cut directly into No. 2 hold, one of the 4th RTR troop-decks, and inevitably sink the ship. With great presence of mind he caused the helm to be spun violently to port, at the same time signaling his intention to the other ship which luckily took the hint and likewise turned away to starboard. The respective stern quarters bumped with great force, like mighty dodgem cars, crushing plating and carrying away rails and part of our deck. Two Asian members of the crew were killed, four lifeboats were smashed and two of our precious fresh water tanks damaged beyond repair, all the contents lost. Henceforth drinking water would be rationed but “Troops” had saved all our lives. It had been a close thing for though both ships were damaged it was considered a miracle that neither was sunk. At the subsequent Admiralty Court case, although the Memelaus claimed that she was trying to avoid the on-rushing Orbita, The Orbita was exonerated. Whatever the truth of it, the innocent City of London was very nearly a tragic victim, going down with all aboard her.

That morning we buried over the side the two members of the crew who had been killed and the next day a third who had died of pneumonia. Although the ships officers and senior ratings were British the rest of the crew were what were known in those days as “Lascars”, mostly from India. They were good seamen and showed no signs of panic in emergency.

After this excitement everyone settled down to a steady training routine. The light tank radio operators, brushing up their Morse Code, amused themselves by intercepting the Aldis messages emanating from the Commodore. Our Padre, the Rev Douglas Owen, had once been a sports commentator before ordination. He and a New Zealand officer created mythical England and All Black rugby teams and, after an intense build-up on the news broadcasts, kept the whole ship in a state of great suspense as over the Tannoy loud speakers they described a ferocious match, complete with injuries and fouls, which of course ended in a draw. The Padre was later to excel himself with a broadcast Grand National, in which even he could not predict the result, whereby a great deal of money passed in and out of the Tote. We were soon, however, to witness a different kind of contest.

The Admiral Hipper

Early on the 22nd December we burst a steam pipe and the ship

hove to for an hour or two, the convoy meanwhile disappearing and leaving

us entirely alone, surrounded by an empty horizon. However, the damage was

soon repaired and we had caught up by afternoon. This being the Sunday before

Christmas the Padre had been hoping to hold a carol service, but the previous

night there had been a real blow so that this morning, though the weather

was becoming warmer, the stationery ship was rolling so heavily that the service

was postponed till next day. By then the sea had abated and the service on

the sheltered after well-deck was well attended. We began to look forward

to a few days break from training over the Christmas holiday, there was to

be a concert and the cooks promised surprises. We were kept on our toes by

receiving an air raid warning which, being predicted for 1330 hrs, allowed

a leisurely lunch for all except the anti-aircraft Bren gunners who, becoming

very excited, eagerly scanned the skies and warmed up their guns with alarming

enthusiasm. However, nothing transpired.

We had seen no sign of any enemy and had no idea whether we were in any danger. The Royal Navy were however aware of the presence far to the south of the German battle-ship Admiral Scheer with the raider Thor and two supply ships. Moreover U-boats had just sunk three ships off the coast of Sierra Leone.

We were powerfully escorted by the eight inch cruiser HMS Berwick and the six inch cruisers Bonaventure and Dunedin and for several days also by the aircraft carrier HMS Furious. She, in addition to her own planes, was carrying boxed aircraft for Takoradi on the Gold Coast (now Ghana). These were then to be flown by stages across Central Africa to Egypt – a prodigious logistic effort. We watched planes flying off Furious and returning, not realizing that they were patrols searching for U-boats. We seldom saw all the cruisers at once for they ranged far and wide, and soon Furious left us for Takoradi.

Meanwhile, the Germans, believing that the presence of Scheer and Thor would distract the Royal Navy, drawing their attention to the South Atlantic, had decided to send out the modern eight inch cruiser Admiral Hipper.

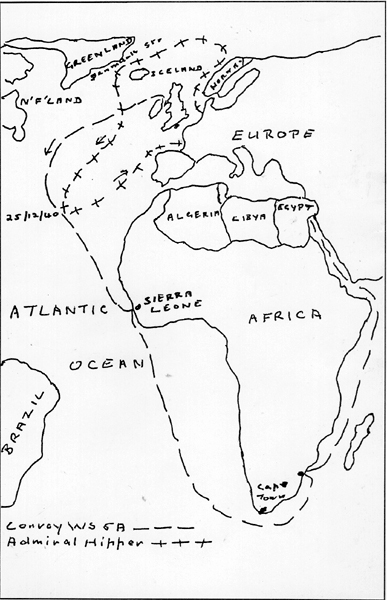

Photographic reconnaissance had already spotted her at Brunsbuttel at the mouth of the Elbe on 29th November but no significance had been attached to this and no special measures were taken to keep her under observation. Thus it was not known that she had left the following day and was creeping up the Inner Leads along the west coast of Norway. She waited until bad weather stopped all flying and then, on 7th December, broke through the Denmark Strait between Iceland and Greenland while it was unwatched. This was the same route into the Atlantic already used by the Scheer and the Thor. While the Scheer had been ordered to attack independently routed shipping the Hipper was now tasked against our convoys. Having twice probed the course believed to be used by our Halifax convoys with no result she headed south, intending to try the Sierra Leone route, but at first was unsuccessful.

On Christmas Eve, as we passed some 700 miles south-west of Finisterre, near the Azores, the Hipper found Convoy WS 5A and, unknown to ourselves and our escort, shadowed us overnight intending to attack at dawn. At first light, however, there was a thick mist and she thought she had lost her quarry. It has to be remembered that at this time no navy was equipped with ship-borne radar nor had the code breakers at Bletchley Park yet managed to crack the naval version of the German Enigma cipher machine. All concerned were therefore largely blind in the early morning mists.

Meanwhile, aboard the City of London, we had enjoyed a Christmas Eve midnight service in the main saloon and reveille and breakfast were to be an hour later than usual.

Thus the occupants of our cabin were all awake but still in their blankets when, just before 7 am, we heard two booming explosions very close together. Springing to the porthole we saw, a mile or two to our starboard and just ahead of the convoy, a very large grey warship silhouetted against a bank of thick mist and moving in the same direction as ourselves. We could quite clearly discern details of her funnels, portholes, bridge and even lifeboats and pinnaces. In that moment of recognition, just as the alarm bells sounded, there were two flashes followed by another double boom from twin turrets. During the few moments it took to run to our boat stations we heard further very heavy and rapid sound of gunfire.

On reaching the deck we could see that HMS Berwick was the only one of our escorts immediately to hand and she, as it happened, was to port of the convoy. She was now crossing our bow at full speed, smoke a horizontal stream from her three funnels, spray flying over her decks and all her forward guns firing. It was a spectacle to stop the heart. Minutes later both ships disappeared into the mist, from where we heard again the sound of gunfire.

Looking around we saw that the Commodore was flying a flag signal and that the convoy was already dispersing in all directions. The Empire Trooper and at least one other ship seemed to be on fire but still moving. At that precise moment there came a roar from below and clouds of steam shot from the engine room hatches and ventilators, while the beat of our single propeller ceased. We had burst a vital steam pipe and lost all power. Luckily nobody had been scalded but it was to be several hours before the engineers, assisted by some army fitters, were able to effect temporary repairs.

We now found ourselves stationary and alone, flying the “Not under Control” signal, the mist meanwhile beginning to disperse. Later, Berwick returned and called us by loud hailer.

Her Captain told us that he had scored several direct hits on one of the enemy main turrets and suffered similarly himself, five men being killed and eleven wounded. Berwick had also sunk a German supply ship, thought to be the Dusseldorf. Hipper had withdrawn and contact was now lost, so he and the other escorts were attempting to round up the convoy. We replied that we hoped soon to be under way and were advised to make for Freetown, Sierra Leone. The Official History considers that the convoy had been ordered to scatter rather prematurely and that it had difficulty in reforming. In fact, several damaged ships, one of which had a very bad fire, went to Gibraltar and the rest were eventually reunited.

The Hipper had been as surprised by the encounter as ourselves but was now aware of the strength of our escort. In view of that, her own damage and certain machinery defects she headed for port. She entered Brest on the 27th , the first major German warship to use a French port. Arriving undetected she was not in fact sighted until the 4th January.

Some time after the departure of HMS Berwick our engines were restarted and we headed south on our own towards Freetown, Sierra Leone. The whole ship now enjoyed a marvelous Christmas Dinner, all the cooks combining to produce really extraordinary results in the most difficult circumstances. By that evening the weather had become very rough again – but we had had our dinner just in time. We continued on our own, with no escort and passing through what we were told was a danger area, for four days until on the evening of 29th December we caught up with the rather depleted convoy which had slowed down to wait for us.

PART III

Africa

On the 4th January we arrived at Freetown, Sierra Leone, where

we anchored in the estuary, well out of range of malarial mosquitos. Here

we stayed for a few days which enabled us to make a better job of the engine

room repair and to take on fresh water to see us through to Durban. We were

also able to send our mail ashore for collection by the next homeward bound

convoy. Unfortunately one of our officers became very ill and had to be left

behind in the hospital ship there. Meanwhile, several large canoes or “bumboats”

laden with fruit came alongside and the colourful occupants slung up weighted

cords attached to baskets. After much barter the soldiers sent money down

in the baskets and in return pulled up mangos and bunches of bananas. One

of these Africans sold the troops a monkey, which he had taught to make a

beeline for the anchor chain and so back to its owner. Just as we were ready

to sail it was reported that a soldier had caught the monkey and hidden it

away. The Captain said that the crew would believe it very unlucky to have

a monkey on board and, having already suffered a collision and other misfortunes,

he refused to sail with this one. Duly found and thrown overboard it was retrieved

by its owner.

By this time we were becoming concerned about our tanks which had been loaded unto a ship called the Mahaseer supposed to have sailed from the Clyde to join our convoy at sea. She had not done so, but we hoped that she would be at Freetown. She was however not to be seen and at a naval conference ashore one of our Captains said that he had seen her in the Clyde and had heard that the tanks had not been properly secured in the holds, so that she had been forbidden to sail. We now became seriously worried as not only was there every possibility that she would fetch up in a different port to ourselves, but after such a long voyage the tank batteries were likely to be badly discharged and damaged. However, there was nothing that we could do about it. In the event, we arrived at Port Tewfik on the 16th February and the ship carrying our transport not long afterwards, but the Mahaseer did not do so until the 18th April. By this time the New Zealanders were already fighting around Mount Olympus in Greece.

Once more at sea we found the cruisers ready to escort us down the coast of Africa, round the Cape of Good Hope with its infamous “rollers” and so to Durban. By now we were all in tropical kit and the crew had attached to the derricks tall canvas tubes which scooped up fresh air and delivered it to the troop decks below. Some of us slept on deck but had to be quick of the mark when seamen cried out “Wash down deck Sah” as they approached with hoses at 5 a.m. Some of the older soldiers, found that they could now tolerate the cooler troop-decks, brought out illegal “Crown and Anchor” boards with which they proceeded to fleece those younger and less sophisticated than themselves. Regimental provost staffs were kept busy flushing out these gambling dens down below and confiscating the boards – and the ship’s crew were kept busy making new ones.

At Freetown there had been an opportunity to send mail ashore addressed to UK. The officers were thus obliged to undertake the rather distasteful but often very moving task of censoring the soldiers letters. We were surprised to find that far from complaining, the men claimed to be enjoying their sea voyage, many describing the food as good in quality and quantity considering the difficult circumstances in which it was being produced. This says as much for the regimental morale as for our Colonel’s constant and determined efforts to improve matters. He would often visit the single galley and once remarked to me that the heat in there was so appalling that he could not remain for more than a few minutes without going outside for air. He now asked me to give him the statistics for the daily sick rate. We found that it was running at a daily average of eight to ten, whereas the New Zealanders were averaging over forty. Probing to discover why we should have an even eight it emerged that we were providing most of the cooks in the combined galley and that these accounted for half our figures, from heat exhaustion. The difference between the sick rates for the two regiments was surprising, for the New Zealanders certainly appeared to be very fit. However, it was a fact that we had daily quite strenuous PT for all ranks and they did not, which may have had something to do with it.

The Cape Rollers lived up to their reputation, being especially awesome when on the beam. A green mountain seemingly stretching from one horizon to another would approach silently and with an unbroken crest to traverse the convoy from one flank to the other, so that each line of ships in turn would rise above the rest, the masts swaying in unison as the hulls then disappeared from view. The swell was irregular, so that these great waves almost always seemed to catch everyone unawares.

It was during this time that I developed severe toothache. So revealing a gap in our resources for, although both regiments and the ship all possessed medical officers none was experienced in dentistry and there was no dentist on board. As the tooth certainly had to come out a medical conference was held in the saloon bar before lunch. Our own regimental medical officer was disinclined to operate on the reasonable grounds that, if anything went wrong, he was not only sharing a cabin but was likely to have to serve with me for some time to come, which would be uncomfortable. The New Zealander likewise claimed that, if he did it and anything went wrong, I would forever more blame the Kiwis for my disfigurement. I did not like this line of talk at all. The Ships Doctor cheerfully accepted me as a patient saying that we were unlikely to meet again after the end of the voyage and until then he could keep out of my way, mentioning in passing that there was a set of dental instruments on board which he had never opened, but there was no means of administrating a local anaesthetic.

The operation was scheduled for 2 pm in the ship’s surgery beneath the poop, adjacent to the Orderly Room, where I sat nervously awaiting their summons. The doctors gathered in festive mood having enjoyed a good lunch; I had confined myself to a cup of the cook’s “game soup”, in reality Bisto gravy. Bill Thornton, the Ship’s Adjutant brought in the Orderly Room staff to witness the spectacle but I was touched to learn later that my own clerk refused because he could not bear to see me tortured. The Troops Officer was summoned to see fair play.

While I was laid out on a white sheeted examination table with medical orderlies from both regiments at the corners to hold my arms and legs and a Medical Sergeant grasping my head, the Ships Doctor opened the case of instruments. Taking from it a selection of forceps he passed these to his colleagues across my startled gaze, as they weighed the merits of each, the convenience and comfort of the handles and the efficiency of its jaws. The possibility, indeed likelihood, of “slippage” was discussed. The Ship’s Doctor called for all to “Stand By” and advanced with the chosen instrument, while the Sergeant thrust what felt like a golf ball between my jaws. I longed to close my eyes but was mesmerized by the approach of the gleaming instrument. It fastened on to the tooth – mercifully the right one – and I braced myself as I felt the doctor tense.

At that moment the ship began a roll which “Troops” later confirmed was the steepest recorded by the clinometer on that voyage. I felt a rapid falling sensation, as though in a lift with a broken cable, feet scuffed and scrabbled on the floor, someone fell with a cry and there were loud crashes as typewriters, sterilizing apparatus and other breakables were hurled to the deck. We rolled ever deeper, the soldiers clamping me tightly to the bench, and the portholes darkening as the sky disappeared. It was clear that we would roll right over and at last I closed my eyes in resignation.

Suddenly I felt the ship lifting rapidly, I reopened my eyes and in the sunlight streaming through the portholes and open door I saw the forceps held aloft, the tooth dangling from them. I had not felt a twinge and everyone was laughing.

For everyone else this part of the voyage was without event, though by now we were all on the look out for the Scheer or the Thor. We saw neither but were entertained by schools of dolphins and whales and great numbers of flying fish, some of which landed on the decks of the ships. We reached Durban on the 25th January, when we were able to send off more mail. Here we had the good fortune to remain in dock for several days while repairs were at last made to our starboard quarter, new fresh water tanks were installed and the missing galley rebuilt. We took on board masses of fresh fruit and vegetables. The bunkers had to be coaled, a filthy business, so that we were glad to be able to go ashore. Anxious enquiries about the Mahaseer and 2/Lieut Vernon-Harcourt, the young officer we had had to leave in Freetown, both drew a blank from the port authorities.

Coming from darkened wartime Britain in mid-winter to South Africa presented an extraordinary contrast. Here it was mid-summer and there were no blackouts, air raids, rationing or visible shortages of any kind. The people of Durban were wonderfully kind and hospitable, a fleet of buses and cars coming each day to take officers and soldiers for country drives, to the races or to various clubs for swimming, golf and tennis. We were allowed to travel free on the trams and the troops made joyful use of the rickshaws. There was even a spectacular performance of Zulu war-dances, unfortunately spoilt by torrential rain. None of the thousands of troops who stayed there would ever forget the generous kindness of the people of Durban. The night before we sailed there was a frantic last minute scramble to get aboard before the deadline but everyone in the regiment made it – though four young officers were obliged to come in through the coal bunkers, the gangway having just been removed, thus providing a pool of duty officers for the rest of the voyage, once their best drill uniforms had been laundered. After we had sailed the South African Military police caught us up in a motor launch with twelve New Zealanders, but unfortunately ten of their own men had to be left behind for good. Two Royal Naval seamen were also returned to their ship by the same means.

PART IV

SUEZ

Leaving Durban with regret we now joined another convoy to

make our way up the east coast of Africa and into the Red Sea. During the

voyage boxing tournaments had been held within each regiment and now, in the

last leg, came the final match between the two unit teams. The New Zealanders

lost by 7 bouts to 3, the last bout ending in farce when, in the third round,

neither of the two enormous heavyweights could remain up- right without clasping

the other and the fight was stopped amidst roars of laughter. Relations between

Brits and Kiwis were always excellent throughout the voyage, friendships being

struck which would endure for years.

Enemy submarines and aircraft were operating in the Indian Ocean at this time so that regular alarms and alerts continued and we kept the anti-aircraft guns fully manned until we were well past Aden, finally reaching Port Tewfik at Suez on the 16th February 1941.

Standing on the dock side in the hot sun, waiting for trains to take us we knew not where, we looked up at the City of London with mixed feelings. So much had happened since we first saw her at Number 5 Dock in Liverpool. By most of the soldiers who had been crammed down in those holds in extreme discomfort, especially in rough or hot weather, she would always be described as “that hell-ship”. Yet, seeing the scars still visible on her starboard quarter and looking up at “Troops” and the old OC Troops gazing down on us from the bridge, the latter for once properly dressed, we felt a certain affection for the old lady, for we had been through much together and, after all, she had brought us here safely in spite of everything. Nobody knew how many miles those ancient reciprocating engines had already steamed and on the one occasion when she had attempted her maximum speed of 15 knots they had given up and nearly delivered us to the Hipper.

Aftermath

We wondered what the future held for the old ship and doubted

whether she would last long so, as we steamed away in the open trucks of the

Egyptian State Railway, the troops raised a cheer for her and she gave us

a farewell toot.

In fact, she was to serve in the Mediterranean, based at Alexandria, until the end of the war, participating in many campaigns. Amongst her greatest exploits was the evacuation of 4,000 troops from Greece not many weeks after we left her. The ship’s company was given the highest praise for this operation, Captain Longstaff and Mr. Macauley, the Chief Engineer Officer, both being awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for their gallantry and devotion to duty. Having survived the hazards of two wars, the City of London ended her honourable and distinguished career by bringing home a full load of Service personnel in January 1946, in her fortieth year of service, after which she was broken up.

The 4th Royal Tank Regiment was less fortunate. When at last in April the tanks arrived and had been put into running order and modified for desert warfare the regiment was sent by train to Martin Bagush and thence to the front. On the way one tank train became derailed, killing two men, injuring five others and damaging four tanks. Thereafter the regiment drove out into the open desert to engage in fearsome tank battles at Halfaya Pass in May 1941 and, having at last been rejoined by B Squadron from Eritrea, the following June. They were then shipped to Tobruk to endure the long drawn-out siege and the ferocious break-out battles in November and December. Although one officer was to win the Victoria Cross among many other decorations awarded, so dreadful were their losses during these latter actions – 34 officers, for instance, becoming casualties out of an original strength of 27 – that they were removed to Palestine to recover and re-coup with Valentine tanks. They returned to the Western Desert in March 1942, in time for the great battles of Gazala and the Cauldron followed by the second, disastrous, siege of Tobruk in June 1942, in which the regiment fought literally to the last tank and was thus totally destroyed, not to be reformed for some years.

As for our New Zealand Gunner shipmates, they

too suffered grievously though they survived till the end of the war. They

joined the justly famous New Zealand Division with whom, after Greece and

Crete, they too fought in the Western Desert, back to El Alamein and on again

into Tunisia and thence across the Mediterranean to end their campaigning

in Italy. That is a story they may themselves tell with pride.