RE, 10 RAILWAY SQDN 1951-52

'YES, WE BORROWED YOUR RAILWAY'

As Remembered By Robin Thorne

The refusal of the State Railways to convey food and fuel oil was the cause of grave concern, especially as the Army Power Station at Fayid was running low on fuel for the generators. The decision was thus taken to take over key points on the State Railways and run British War Department trains either by consent or by force where necessary. The task of Transportation Branch was to keep the Canal Zone Garrison supplied with all the necessities if life, against the background of a hostile population, who were to engage in many acts of sabotage against Army Trains and the Sappers manning them.

The units involved were 10 Railway, 53 Port and 1207 Inland Water Squadrons, with 169 Railway Workshops Squadron in support. They were eventually supplemented with about 200 Reservists who were activated and used to take over most signal boxes, marshalling yards and port operations from 1952 onwards. I shall however confine my article mainly to the time before those welcome reinforcements arrived.

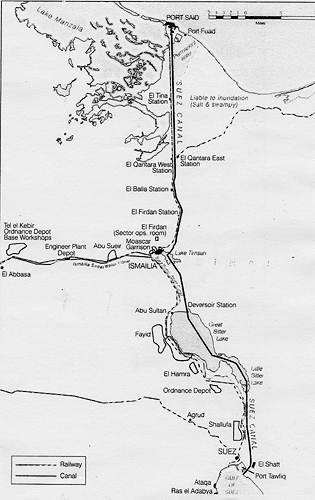

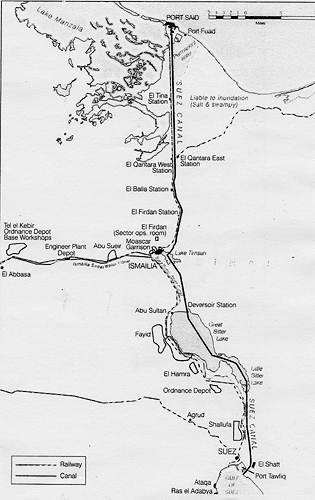

The Squadrons were tasked to move oil, food and munitions from the Military Port at Adabiya (South of Suez) to Depots, Storage and Power stations located between Suez and Port Said and also to the massive stores depot at Tel El Kebir. Before the Treaty was abrogated, engine drivers of 10 Squadron were allowed by the Egyptian State Railways to work Army freight trains over the State Network in the Canal Zone and also to Cairo for engine wheel balancing, providing they were accompanied by a State Railway Conductor. This was stopped as a political move in August 1951 but by this time 10 Squadron had acquired much useful knowledge of the network they eventually took over. The Squadron was located in a tented camp 20 miles south of Suez beside the Gulf of Suez; an ideal location for operating the Dock railways and also the Adabiya – Ataka Military Railway. The Dock labour force was intimidated into not working for the British, so to counter this, 53 Port Squadron was moved in. 10 Squadron had many homes. But eventually ended up at Fanara on the side of the Great Bitter Lake – a good central point from which to conduct railway operations. Incidentally, one of the sheds we took over was where the Public Hangman operated!

In Egypt, the British military railway operated to and from the military port

of Adabiya to the Egyptian State Railways signal box at Ataka. This was the

exchange point in times of peace for WD traffic destined for various depots

in the Canal Zone and was a joint operation between local Egyptian Rail Staff,

Movement Control and 10 Railway Squadron. After the abrogation of the Treaty

and the refusal of the State Railways to convey WD traffic, the method of working

changed. The Egyptian signalman at Ataka and the local movements clerk did not

take duty and the military railway was effectively worked as a long siding from

Ataka to the portside of Adabiya.

After our essential freight movements were refused by the Egyptian State Railways, the officer commanding 10 Squadron, Major Alexander, decided that we would not lie back and wait developments. We paraded in battle order and several parties were detached to seize railway engines from the Suez Locomotive Depot. Several engines were already in steam, so we moved them to the local Adabiya-Ataka Military Railway, located about 10 miles south of Suez. Pressure was exerted on a political level and the engines were very unwillingly returned by us to the Depot. The episode did however demonstrate to the State Railways that the British forces would not take matters lying down.

Each train which left the Army railway at Adabiya to go on to the state railway network was manned as a complete self contained travelling unit. Its crew consisted of a driver, fireman, a railway signalman (known as a travelling blockman) and a minimum escort of three fully armed infantrymen, normally from the Royal Sussex Regiment.

The blockman travelled on the engine in order to instruct the driver of action needed at each signal box, level crossing and other route knowledge problems. This could mean that a sergeant locomotive driver would be expected to obey the orders of a Sapper blockman. It sound odd, but railwaymen knew the way it worked.

We were all trained soldiers and combat engineers, but when crunch time came, we were professional railwaymen in Army uniform!

Back at camp, the usual rules and respect applied. Once our trains had left the Army railway, it was necessary to take over control of each signal box as we came to it. The travelling blockman, escorted by the infantry soldiers, had to assess the Arabic Signalling Frame and Diagram of each box before setting up the route for his train. The boxes had mostly been abandoned by local staff and routes set in the wrong direction. Since our Arabic was non[existent, it was necessary to draw a picture of each number on the Signal Box Diagram and then find a similar looking signal lever. Once the signals had been operated we returned to the engine, gained the double line and proceeded to the next signal box. On a double line the points were usually trailing which meant that even if they were lying in the wrong direction, it would be safe to run through them.

Historically the State Railways were very British in design and operation, especially their Rules and Operating Instructions and they always signalled Sapper trains as “vehicles running away right line” which corresponded with what we would have done under similar circumstances in the UK. The fact that the levers and signalling diagrams were annotated in Arabic was a problem, but with the Egyptian railways being based on British practice, and also the fact that most of our signalmen were national servicemen from busy civilian signal boxes who could reas routes on a diagram and translate that into movements on the track made our life so much easier.

The State railways owned No. 1 Signal Box was the key to operating trains in a northward direction. During January 1952 it was decided that the Box would be fortified with a permanent 10 Squadron signalman. This went on for several months, the crew of the box being supplied by armoured car with the necessities of life including toilet facilities. Relief of signalmen and escort was covered by the same means. After shots were fired at the box, a combined army group flattened the area around it to deny terrorist the cover needed to fire on the installation.

As with many things, the Egyptian railways followed the British Railways system

and many signal boxes were built on station platforms. They were regarded as

flash points and dangerous places to take over. The platforms were usually full

of very disgruntled passengers, who hated the Sapper railwaymen, not only for

the political situation, but because the WD trains forcing passage were usually

the cause of their own trains running late or being cancelled. The effect would

be rather like a foreign Army trying to run trains from London to Brighton,

with the resident railwaymen and the local population doing all in their power

to stop it happening.

1952 saw a worsening of attempts to mine the railway and take out track, causing some very bad derailments. One of the mined trains blocked the line totally so the OC, Major Alexander, decided to build a new railway round the derailment.

In between these railway duties we had to carry out 24 hour guards of filtration plants, hospitals and of course our own camp. On one occasion when I was Guard Commander, one of my men refused to go out on patrol (remembering we were on active service) and when my direct order to return to duty failed to resolve things in his mind, I placed him under close arrest. He told me in an even tone that he just could not take it any more – the pressure and danger was just too much for this 6ft 3in Sapper. He the key to a cell, locked himself in and gave me the key. He was dealt with locally, only receiving 28 days detention, rather than the two years imprisonment a Court Martial would have awarded.

So life went on until 1956 when the Canal Zone was finally evacuated with the new headquarters of the Near East Land Forces being in Cyprus.

In 1965, the RE Railway Squadrons were re-badged to the Royal Corps of Transport and then passed on yet again to the Royal Logistic Corps. At handover, the RCT acquired from us the Transportation Centre at Longmoor together with 8 Railway Squadron, 17 Port Regiment at Marchwood together with three port squadrons, a port squadron in Singapore and a lighterage troop in Cyprus. I Railway Group was also handed over together with 100 locomotives, 2,000 wagons and 645 miles of track.

Since then, the capacity to operate railways in time of conflict

has been whittled down to one troop of 17 Port Regiment, assisted by the various

small specialist units. Is that enough? Recent experiences in both Kosovo and

the Basra Port area of Southern Iraq show that the Army does need to retain

a reasonable railway expertise, so although it will not be an RE responsibility,

one hopes that the powers that be will look back on our Corps history if guidance

and perhaps inspiration is required.